Our Chernobyl

Craig Mazin’s Chernobyl — a brutal, beautiful, frightening piece of film making — tries to grasp in a net of images and story the worst nuclear disaster in human history, an accident that was in a sense the inaugural event of the Anthropocene: the first moment in which we humans suddenly experienced as an actual reality our own power potentially to render the world, the whole world, uninhabitable. The HBO series has two basic aims: first to convey the human reality of the story: the fear, pain and suffering experienced by those who went through it; second, to try to plumb its meaning; to figure out what the disaster was all about. It fails on both counts.

The first failure is admirable and forgivable. The series conveys with luminous clarity the texture of life before, during and after the disaster. But what the people suddenly caught up in the vortex of nuclear disaster actually went through is, in a real sense, not possible to convey. ‘The words are all wrong’, says Lyudmila Ignatenko, the wife of Vasily Ignatenko, one of the firemen who died in agony from radiation poisoning two weeks after rushing to the conflagration when Reactor 4 exploded in the small hours of 26 April 1983. Not the Lyudmila in the series, the real Lyudmila; the actual, historical woman whose account provides the inaugural story in Voices from Chernobyl, the social history on which the HBO version draws. She tells her story simply, even beautifully, but her words are of a reality that is unimaginable. ‘It’s all so very mine!’ she says of the experience of watching the man she was in love with basically liquify, day by day, on the hospital bed in front of her. ‘ It’s impossible to describe! It’s impossible even to write down! And even to get over.’ The worst and most painful parts, she says, she can’t even remember. It comes to her ‘in flashes, all broken up’: painful details, lodged in the body, toxic and ineradicable. A survivor of an experience whose most intense reality lies beyond words, even beyond memory.

Lyudmila

The second failure is the result of calculation, of smugness, of thinking you know the answers. Instead of conveying the full and terrible moral complexity of what happened, the series turns the story of Chernobyl into a comfortable and heartwarming narrative, into a parable about courageous, truth-seeking scientists confronting bureaucratic ignorance and Soviet stupidity. In a way, radioactivity becomes a baleful metaphor for truth itself: The nuclear reaction surging catastrophically out of control in the core, in response to the imperious arrogance of the buffoonish Anatoly Dyatlov; the chunks of toxic graphite littering the reactor site, nakedly contradicting the blind refusal of officials to believe that the core could explode; deadly isotopes sifting gently down from the sky or seeping up from the earth, while the government assures everyone they’ve got everything under control — all these become metaphors for the inevitability and the unstoppability of Truth, its refusal to be contained by bureaucratic obfuscation and propaganda. The gift of Chernobyl, Legasov admonishes his official superiors, is that it shows us that the truth does not care about our needs or wants. ‘It does not care about our governments, our ideologies, our religions. It will lie in wait for all time’.

An imaginary scientist

There are three problems with this. The first is ironically enough, that it’s a lie. As Masha Gessen pointed out in her rather angry New Yorker essay the makers of Chernobyl can only get the story to carry its uplifting message by twisting real events out of shape: through making Valery Legasov a far less ambiguous, compromised figure than he really was; through the many ‘repetitive and ridiculous’ scenes in which heroic scientists confront truculent bureaucrats; through the totally invented, totally improbable figure of the doughty Ulyana Khomyuk, an imaginary scientist straight out of Hollywood fantasy; and above all through staging an entirely fictional, impossible trial where Legasov theatrically unveils, in spite of KGB efforts to keep it quiet, ‘the truth’ about the design flaws in the RMBK control rods that finally led to the meltdown.

But that’s not the truth, it turns out: though Gessen does not mention this, the series’ diagnosis of the ultimate causes of the disaster — that a paranoid Soviet government censored evidence about the dangers of those graphite-tipped control rods, keeping the information out of the hands of its own scientists — is a complete misrepresentation. The reality is rather more tawdry: the Soviet nuclear community knew about that design flaw, but just never acted upon it. They just didn’t think it would ever really be a problem.

Secondly, the implicit historical exceptionalism in the series — the repeated suggestion that the train of events leading to the accident and the attempts to cover it up is somehow specifically Soviet — does not hold water. The reality is much more unsettling. A glimpse of that picture is offered, for example, in Karen Brown’s account of Western collusion in the attempts to downplay the seriousness of Chernobyl’s aftermath. It is not only in the Soviet sphere, it turns out, that the warnings of scientists get ignored, or unsettling realities about the danger posed to our life on Earth by own industrial civilization are passed over and denied. (But you know that. Today, in 2019, you know that). And if truth be told, one thing the series does give an inkling of is the decisiveness of the Soviet response once it realised what it was dealing with. Would a society governed by market forces be willing or able to scrape 30 centimetres of topsoil off thousands of hectares of farmlands? Or send in more than half a million civilian and military personnel into a nuclear fall-out zone to evacuate an area and clean it up?

Here’s one clue: the contingency plan of the government of the Western Cape in South Africa, in case something bad happens at Koeberg, the ageing nuclear reactor built just about astride a geological fault a mere 50 kilometres north of my house, involves the evacuation of the local population by minibus taxis. That’ll work!

Are these liberties with the truth poetic license, an attempt to simplify the story so that it can be told more effectively? I don’t buy it. For the overall artistic consequence of this moralising spin is that it causes the story to drift away from its emotional centre. This is my third, and in a way my most serious objection. If dramatic licence was required to impart a sense of drama to an otherwise dry or overly complicated historical record, it would be understandable. But in this case, it does not really seem warranted. People battling frantically to contain a runaway nuclear reaction? Soldiers and miners risking their lives to avert disaster? Hundreds of thousands of lives shattered by sudden forced evacuation, or blighted by creeping illness? It’s not as if this is a story that needs to be spiced up or given artificial dramatic interest. And in fact, there is a gradual leaching away of energy as the story winds on and the initial wrenching scenes of disorientation and fear give way to the battle between apparatchiks and scientists, and the trial’s schoolroom lecture about how a nuclear reactor works.

This, for me, is the real issue with Chernobyl. Because what’s really strange about it is how it allows some of the most emotionally compelling and unsettling aspects of the crisis to slip through between the lines. It is as if the meaning of what we see is right there in front of our eyes, but still remains unsayable. For the drama and the power of the story does not come from this staged confrontation between scientific truth and bureaucratic lies. It comes from the uncompromising and visceral way in which it conveys the sense of a world suddenly gone nightmarishly out of control. The central scenes in the series were for me dreamlike: instantly recognisable though I had never been there; refusing to be banished from memory even days after viewing. The panic and chaos in the control room. The fireman curled up in agony around his hand, burned by invisible rays from the graphite. The divers endlessly plodding through the claustrophobic dark in the waterlogged basement of the reaction, listening to the chattering scream of the dosimeter. The cleanup squads, blundering about in the rubble on the roof above the yawning maw of the reactor, racing against time. Lyudmila Ignatenko and her husband. People thrust into a world that has suddenly and incomprehensibly become an inferno; trying heroically and sometimes futilely to deal with dangers they do not completely understand; dangers that they cannot see; but a danger that they slowly realise they brought on themselves. Human technology — yes, human science! — revealed as a pandora’s box from which invisible horrors emanate, malign and unstoppable.

Think about it.

A world turned into inferno.

Dangers we cannot see, that we do not know how to control.

A world at risk of becoming uninhabitable because of our arrogance, our ignorance, our refusal to heed warnings. Our foolishness.

Warnings that were all around us.

The thing about climate change, and about the ways it will change our lives is this: we can’t blame the Soviets. And there won’t be a grimly decisive Boris Shcherbina to save us. We’ll be on our own.

Outside Parliament

Picture: Poloho Selebano

I arrive at beginning of the #feesmustfall march on CPUT’s Cape Town campus a little before 12. I’ve Uber-ed here, deciding to leave my car in the Gardens Shopping Centre not far from where the march will end. A good decision, as traffic is already disrupted, with hippos and other police vehicles lining the street up and down the Keizergracht. It’s the hottest day of the spring so far, with a blazing hot sun and no wind. Perfect marching weather!

The march has been called by the Cape Peninsula Technicon, but it has swelled to include a number of different groups, including #feesmustfall students from UWC and workers campaigning for an end to outsourcing. The plan is to proceed to Parliament, where our embattled Minister of Finance is about to present his mid-term expenditure framework, and to present him with a memorandum of student’s concerns. After the fractious days of the last few weeks, and the fears of polarization on our own campus, this has seemed to me and many of my colleagues to be an important opportunity for trying to build bridges. If the struggle around student fees continues to be framed as an adversarial struggle between students on the one side and university management on the other, we’re all in trouble. The ability of this movement to lead to positive change depends, or so it seems to us, on our ability to construct a broader alliance of students, staff and University management around (among other things) the need for better funding for tertiary education.

I have been particularly concerned by a dangerous dynamic unfolding on campuses. Now, as during last year’s protests, a prominent role has been played by groups of angry young people indulging in reckless, even violent acts. Alongside open, inclusive, ‘intersectional’ approaches there have also been chauvinistic and coercive ones. How these different aspects of the students movement relate, and how they will work out, I don’t completely understand. But it seems to me that these tendencies are exacerbated when students feel alone and unsupported. If they feel less isolated – if they know that teachers and other staff on campus support their broad demand for more accessible, more relevant education, or are simply there in sympathy – this may prevent the destructive dynamic of increasing conflict. So this seems to be an important moment. At UWC, FMF students rather peremptorily instructed our University management to join them. University management (unfortunately, in my view) declined. And though that is a disappointment and (I think) a lost opportunity, I’ve decided to come in my own capacity and be part of this thing.

CPUT is alive with young folk – I am not good at estimating numbers, but it looks like upward of three thousand people, scattered on the grass and on the terraces behind the admin building. The event has that sense of organized chaos so typical of large, free-flow crowd events. Peace monitors are everywhere in evidence. There is also a visible presence of marshals. At the same time it’s a situation where it’s going to be very easy to lose track of any friend or colleague you want to meet. Calling people on phones is useless, as the noise levels are too high; and I’ve already met two people whose smartphones have simply shut down because of overheating. High-latitude technology. But soon enough I bump into some UWC colleagues. I’m told that as academics, we have been asked to ‘join the clergymen.’ This is not a thing I’d do instinctively – I’m more one of your rootless, secular cosmopolitans – but today my intention is to do what I can to help make this thing work. Eventually I find someone who looks like a clergyman (male, frock, white dog-collar, seems legit) and stick to him.

The mood is ebullient and festive. Someone with a loudspeaker in the centre of the crowd is briskly addressing us all, enjoining us all to be disciplined and to not harass other marchers. I am glad to hear this, given that there has been talk of disrupting the DASO march also taking place today. Very little in the way of overtly political signage, though EFF’s red and PASMA’s green is everywhere in evidence. Most signs are hand lettered and improvised. The biggest one I can see calls for ‘Free Education or Death,’ which frankly sounds like a bad idea. Someone else has a big crucifix. There is also a small cardboard coffin tossing like a little ship on the heads and shoulders of the crowd, bearing a picture of Education Minister Blade Nzimande.

Picture: Ashraf Hendricks, Groundup

Then we’re off. A little early, according to my watch, and surprisingly quickly. At the beginning it’s more a jog than a march, and pretty soon I’ve lost touch with my clergyman. No matter, since I have made contact with friends, students and colleagues, and also with my sister Marijke. She’s there with her own neatly printed sign saying ‘Siyavelana nabafundi bethu’ – we hear / feel our students. (Mine says, rather unimaginatively ‘Education for Liberation.’ ) A group of colleagues have transliterated Marijke’s slogan onto a long cloth banner and are endeavouring to walk in line carrying it at the front of the march. For a while I try to join them in this enterprise, but there is simply too much jostling and after a while I fall back from the frontline, moving with the crowd.

In all of this the festive, jovial, playful mood of the young people is evident. The crowd is diverse, composed mostly of CPUT students; all full of the joys of spring. There is much improvisatory playing with protest songs, greatly enjoyed even by those who do not (or, like me, are unable to) take part. None of my generations’s lugubrious Senzeni Na for this crowd; the songs are snappy, cheerful, brimming with energy. Early on in the march, we are suddenly pelted by light little pink packets. These seem to contain face masks. For teargas, someone explains. More pink packets shower us from a different direction. Condoms. (Apparently the lubricant provides relief against teargas. One lives and learns).

Police are monitoring us closely. Initially there are some attempts on the part of the police to get us to march in an orderly fashion with marshals in front but this proves futile. Fortunately, this does not spill over into violence: marchers, peacekeepers and police all seem to agree that the thing to do now is to get to Parliament as smoothly and pleasantly as possible. We move fairly chaotically but still smoothly and rapidly up Keizergracht, past the parade, and up Buitenkant.

Passersby and onlookers seem irritated (especially those who are sitting in cars, mired in a traffic jam while the students flow around and past them). Others seem to approve and wave or applaud students from balconies. A lean and wiry fellow with a big Afro leans out of a high window and makes a black power salute, which gets an appreciative response. Roadside vendors prudently shutter their stalls. What strikes me is the multitude of scripts already in play. For us in the march, this is a jovial performative occasion, a moment to be seen and to be heard; for those in the cars and in the shops, we are an irritation and possibly even a threat.

Surprisingly quickly, we arrive at Parliament. The van of the crowd collects at the Stalplein, by that bombastic statue of Louis Botha on his horse. The crowd is large and fills up all of the last street block of Roeland. I suppose now is the time to go seek out my clergyman, but it’s a hot hot day, the crowd is jam packed and we’re probably in for a long wait. I head over to the other side of the street, where St Mary’s Cathedral and its adjoining palm trees promise some shade.

Photo: Ashraf Hendricks, Groundup

And there we wait. It’s not even 1 PM, (the march by which the march was supposed to start), so it’s a long wait. More a people arrive. The singing continues, with increasingly baroque variations. An enterprising couple of young white guys with the sporty, relaxed look of surfers walk back and forth between Roeland Street and the Stag’s head, carrying large plastic containers of water. The more forward-thinking people in the crowd bring out umbrellas to protect them from the sun. A helicopter appears and starts circling ominously, clattering by alarmingly close to the local high-rise buildings. Other than that, the mood is relaxed and calm. Those who are not singing get out their phones; start posing for selfies and checking their feeds.

I do the same: not for selfies, but for my WhatsApp thread and Twitter. Some journalist reports that Pravin Gordhan has indeed come out of parliament to meet with the marchers. Good man. Pravin is the man of the moment in South Africa, a solid little point of stability in a sea of venal bunglers. He seems to have made sympathetic remarks, telling the students he’s been in their position too. Later on, more tweets convey nuggets from his speech inside parliament; again, he takes a noticeably sympathetic stance. An encouraging sign, I think.

Time passes, and it’s not clear what happens now. Do we march back to CPUT? Or just wait for the 3PM curfew to roll around? What happens then? I connect up with two colleagues from PLAAS; we share office talk and thoughts about current events. People start drifting off. I am feeling tired and hungry. I get a message from my partner; my stepdaughter Ruby is sick and needs to be taken to a doctor. I say my goodbyes and leave Roeland Street.

Later in the day, I monitor things on Twitter and on our collegial WhatsApp thread. All seems well. Someone posts a lovely picture on Twitter of of a group of students sitting on a police nyala in the heat of the day, completely casual and at peace alongside the police. An image of a moment of harmony.

Picture: Ashraf Hendricks, Groundup

Meanwhile, Gordhan is making constructive gestures inside Parliament, promising R 17 billion more for tertiary education. Some journalists notice Zuma nodding off. Others report that Zuma’s cronies are looking bored and distracted, checking their phones. Maybe they’ve got other fish to fry, I think, than what happens in Parliament.

Then at 3 PM sharp, a colleague posts on WhatsApp. The fucking cops, she says, have just let rip with stun grenades and rubber bullets. What’s going on? “Fucking mayhem”, offers one colleague. “Fucking chaos”, says another. Someone reports “Rubber bullets down the side streets.” There was no warning, my colleagues say. The police just started shooting. There was no order to disperse.

Picture: Ashraf Hendricks, Groundup

Oy vey. Audio clips get shared: scary snatches of gunfire sounds, screaming, angry shouting. Images of students running, throwing stones, of clouds of tear gas, of spent cartridges lying on the road. Stories also filter in on Twitter. Pictures of discarded shoes and broken or crushed sunglasses. What’s going on? eNCA reporters are posting clips on line, but they seem to be caught in a different reality, with a rattled Annika Larsen reporting the event as if the students had been the aggressors, and describing the march as ‘a standoff’ with students (why a standoff? They presented a memorandum and it was accepted by Pravin!). Other news organisations report that ‘parliament is under lockdown.’

Photo: Annika Larsen

From there things go the way they always go at such events: mayhem, injuries, running battles in the streets. Students threw stones at plate glass windows. Other students shouted at them to stop. A student got hit in the head by a brick thrown by another student. The violence spread down Buitenkant and onto the Parade. People stoned a bus and looted a Truworths store in Adderley street. Meanwhile, various eyewitness accounts by colleagues and strangers have the police moving up Roeland and its side streets, shooting indiscriminately at anything that moved.

Groundup estimates that the students involved in violence did not number more than 100.

I don’t have more valid insights into what happened here than anyone else who took part. I was far from the front lines, and I was not even there when the violence broke out. But I do have two observations:

First, it’s worth reflecting on how the violence started: One theory is that as the protest neared its rather anticlimactic end,and has students got rowdier and more restive, the coffin bearers decided to set fire to their coffin and throw it over the police line. This seems to have been the trigger that set everything off. You can see footage of this act online. To my eyes the coffin looks small and shabby; a little battered after its long passage up Roeland Street. A small knot of fire roils fiercely at its centre. There are angry shouts; things already look badly out of hand. The marchers surge forward and lunge towards the line of police officers standing behind their perspex shields. The coffin flies straight over the police line and falls harmlessly on the ground behind them. As a piece of protest theatre it is to my mind rather unimpressive. But as a moment around which the march could pivot into violence it is decisive. The police react instantly, letting off a barrage of rubber bullets and teargas, and within three seconds the whole street has slid into a chaos.

Later, posts do the round on Twitter, saying the cops had no choice, the students had thrown ‘a burning coffin’ at them; a depiction sounding far more dangerous and exciting than the prosaic reality.

Other accounts say that the police moved the Nyala with students on the roof and braked suddenly so that a student fell off; there are even allegations that the Nyala almost drove over the student who had fallen. On the video these actions appear either dangerously careless or quite deliberate. This may have been the event that triggered the coffin-throwing. As usually, there are a mass of sometimes corroborating, sometimes conflicting accounts. Fog of war.

Perhaps poor planning had something to do with it. As one colleague later remarked, in the old UDF days you would have made sure that there was also a leadership who could lead the march away from Parliament in time for the 3 PM curfew. Certainly many accounts of the last moments of the march indicate that groups of students were getting rowdy and defiant.

It is also clear that at this march, as on campuses all over the country, there were people – some students, some perhaps not – who did want some sort of violent confrontation. But during the time I was there they were far from setting the tone. On this particular day, it seems to have been the overreaction of the police that provided the tipping point and opened the doors to the script of violence. In my opinion any public order police worth their salt could have de-escalated the coffin-throw. A hand -sized fire extinguisher could have done the trick. With some fast and canny thinking, and co-operation with the leadership of the march, it should have been possible to end the day peacefully. But this did not happen. Instead, the police seem to have treated the coffin incident as the trigger that gave them permission to use force, and then used means of dispersal almost guaranteed to tip the day over the edge into violence.

Secondly, and in a way much more importantly, what strikes me most of all is what happened within a few short moments to the framing of the incident.

A day that initially developed as a certain kind of public democratic performance (a peaceful march, improvisation with protest songs, a meeting with a Minister, a speech in Parliament) was in a space of ten minutes transformed into a narrative of conflict, violence and securitisation. Students running amok. Stones heaved through plate glass windows. Passers-by assaulted. “Parliament under lockdown”.

The essentially good natured tone of most of the march, and the essentially serious and earnest response from the Finance Minister: these disappeared within moments, replaced by the aftertaste of teargas and burning rubbish in the streets; by anger at violent police and irresponsible students.

Who is served by this? It does not serve the students, or their cause. It does not serve the universities and technicons. It does not serve the Minister of Finance, and definitely not Parliament.

It serves those who co-conspire to create violence. It serves those for whom public disorder has its own rewards. It serves the chauvinistic agenda of groups like Black First Land First, whose members have in the past called for ‘fire’ to be brought to our Universities. It also serves those still defending white privilege, who prefer to see the students simply as thugs and hooligans. It serves the securocrats, and those (including those in our Cabinet) who believe that forceful repression is what is needed to make the problems go away.

It closes off, from the left and the right, the opportunities that still exist to create a meaningful and transformative politics on the basis of our students’ movement.

This is what is happening to our democracy.

Photo: Ashraf Hendricks, Groundup

At the fitness club

This is just a note to say that the management of the club and I are in discussion. I am hopeful that we may be able to resolve matters.

For now I just want to say that my impression that VA did not take the events with sufficient seriousness may not have been entirely correct.

I now understand that a lot was going on behind the scenes that I was not aware of.

I have had a very long and detailed discussion with VA’s management, who have indicated that they were as horrified to read my account of what happened on 5 February as most of you have been and that they do take the matter very seriously indeed.

In particular, I must say I am satisfied that VA are quite sincere in their public statement that they have a zero tolerance attitude toward racism; not only in general but also in this case.

I may bring the original blog post back (quite aside from the matter of VA’s attitude, it still raises important questions about white rage and racial power in this country); but I also think that in all fairness I need to make sure that my representation of the club is fair and accurate.

I really appreciate all the support I have received and hope that it will be possible to use this blog to continue conversation about race, ‘listening’, power and change that we so desperately need.

imagine

The most thought-provoking words spoken at the Boksburg Inequality Conference that we and our partners hosted in Gauteng last month were uttered right at the end, almost as an aside, by the conference’s closing speaker, Neva Makgetla. Reminiscing about her days studying philosophy in East Germany (as it then was), she said that what had struck her was that that the original motivation of those who had tried to create a socialist society – the promise that they had struggled to fulfil – was that socialism would enable a change in the quality of human relationships. But in practice, trying to make a society work, they decided to focus on material things. Money, social services, schools. Perhaps here in South Africa, she said, something similar had happened. The struggle against Apartheid was linked to a dream of what could be possible in the new society, the possibility of something qualitatively different from the fear-filled disconnections constituted by Apartheid. But a country had to be run, programmes designed. And this is what we’re left with, she implied: BEE and social grants.

It was a sobering comment, for it made me think that perhaps we, the organizers of the conference, had somewhat lost sight of our topic. The conference had been organized in order to try to put the issue of inequality more squarely on the South African policy agenda. All too often, discussions about social issues in South Africa proceed as if poverty is a residual matter, the result of some people somehow being left out of economic growth: as if all that is required is to provide them with the assistance and opportunities that are needed to raise their incomes (the current reach-for-my-revolver term is to ‘graduate’ them) above some (usually unspecified) poverty line.

We wanted to challenge those assumptions. We wanted to argue that the central and most urgent issue facing South Africa is not poverty but inequality; and that in South Africa, poverty and inequality were structural. That our economy, while generating wealth for a few, is also a poverty machine, perpetuating and exacerbating steep and deeply rooted inequalities that threaten the basis of social stability and growth. We wanted to use the conference to cast a spotlight on this trend: to ask what kind of society was emerging, and to invite participants to explore what alternatives were possible. Could we imagine a different society, with different values? What would such a society look like?

I was reminded of that aim on the first morning of the conference, when the organizing committee met in the Birchwood’s faux-Italian coffee shop to discuss the start of the proceedings. The conference would be opened by Deputy President Kgalema Mothlante (on DVD, the man himself being required at the ANC NGC in Durban) – after which there would be a recital by performance poet Flo. Flo was there, a shy, burly man with a ready smile. We chatted with him about his plans for his performance, and asked him what he thought he would recite. What would his poems be about? He thought for a moment and said, oh, social issues. And love. There was a moment’s embarrassed silence. Love? Well, I thought, perhaps that was precisely what we were here to talk about. All my relations, and the world they exist in.

I was reminded of that aim on the first morning of the conference, when the organizing committee met in the Birchwood’s faux-Italian coffee shop to discuss the start of the proceedings. The conference would be opened by Deputy President Kgalema Mothlante (on DVD, the man himself being required at the ANC NGC in Durban) – after which there would be a recital by performance poet Flo. Flo was there, a shy, burly man with a ready smile. We chatted with him about his plans for his performance, and asked him what he thought he would recite. What would his poems be about? He thought for a moment and said, oh, social issues. And love. There was a moment’s embarrassed silence. Love? Well, I thought, perhaps that was precisely what we were here to talk about. All my relations, and the world they exist in.

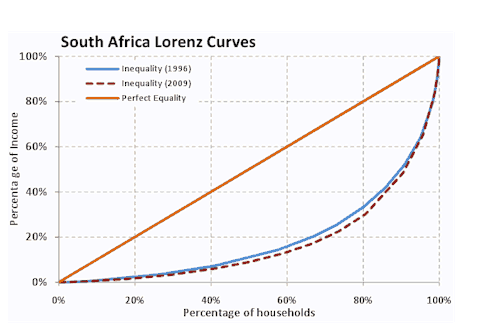

In the event, Flo’s poems were moving, thought provoking and disarming, and did their part to break the ice and get things moving. But pretty soon his words were forgotten, and the participants went ahead, doing what people do at poverty and inequality conferences: considering Lorentz curves, analysing political systems, discussing job creation and rural development. And at that level the conference was, as conferences go, successful. Makgetla’s presentation showed clearly how considering poverty on its own, in isolation, leads to narrow policies focussing merely on particular marginalized groups, while a focus on inequality leads to much more searching questions on the need for social transformation. Other presentations illuminated various aspects of the structural roots of inequality – the legacy of Apartheid, the failure to embark on an employment-intensive growth path, the continued dominance of capital- and energy intensive sectors, and the enormous levels of concentration and centralized corporate power in the formal economy. And there were searching discussions about particular policies and instruments – social protection, small farmer development, community work programmes – that could address these problems.

But in the end, listening to Makgetla’s closing words, I realized that we too, by concentrating mostly on the material, monetary aspects of inequality and poverty, had missed the opportunity to think about the nature and quality of social relations. Sure, there were some good analyses on gender and power relations in labour markets, and on the politics of pro-poor development. But most of our discussions had focussed on material resources, on institutions, on money and social goods. Granted, this was not a poetry conference. We were social scientists, government policymakers, development practitioners, community organizers; not philosophers or novelists. We talked about the things we knew. But what about the more elusive issues? What about thinking about the kind of society that was emerging at more moral, existential or ethical level? What about the obligations and bonds between citizens? What about identity? What about the cordoned heart? What about the structures of feeling, non-feeling and disconnection created by how power, money and fear move in this harsh land? In my own presentation at the conference, I had closed by asking what the scope was for a different project – not technical poverty management, or adversarial populist struggle, but on civic solidarity. Stirring words. But how does one even start thinking about how such a politics might look? Somehow, it is hard to thinking about this issue without getting lost in clichés and in potted thinking.

Hence this essay. My concern today is utopia; or rather, how to find a space for utopian thinking that can have grip or traction in this world. This blog is in the first place concerned with the myths we live by: the lenses through which we look; the resources at our disposal when we try to see what is found there, to imagine what it means, and to dream what’s possible. And in the case of thinking about ‘equality,’ about social relations, it’s hard to find a way of speaking that does not cause us immediately to get lost in prefabricated stories. Analyses of monetary inequality are all very well, but they are mistaken when they confuse the smooth curves that map the distribution of resources in society for social inequality which, as Charles Tilly has pointed out, is a thing of sharp distinctions, pregnant hierarchies, small differences with huge consequences: the difference between black and white, between master and slave, boss and employee. (Or to cite an example close to home for me, permanent university staff and talented researchers still on short-time contracts after 10 years of hard work.) The economists’ conception of perfect equality (everyone has the same income) is useful as a mathematical hypothesis, but it kind of misses the point. Utopian dreams of brother / sisterhood and inequality are deeply compelling (I still get choked up by that Lennon song…) but they’re closed, dislocated fantasies, shaped more by infantile longings for things not to be real than by a gritty assessment of what’s possible. And don’t talk to me about the South African variant: the way talk about racial relations shades so soon into sentimental fantasies about reconciliation, colour-blindness, impossible projects of reparation or essentialist lamentations about how terrible it is to be white. It can be fun for those who do it, but it does not offer much help for those who have to learn to get along, accomplish tasks, feed kids and run businesses in a world in which difference and antagonism are irreducible, real, and maybe even valuable.

So what can we imagine? What can and should we want? I don’t think I have answers. What I have is some disconnected dots; and my guess is that thinking about them may not give me a route, but at least it may help us get a sense of how the map looks, and the lie of the land.

So bear with my meandering argument here. A good place is to start with where we are. Specifically, the Rosmead shopping centre, in Rosmead Road, Kenilworth, where academic Gubela Mji, head of the Centre for Rehabilitation Studies in the Faculty of Health at the University of Stellenbosch Health, was brutally assaulted in September of this year. No-one knows what happened: Ms Mji was stabbed and had received blows to her head severe enough to leave her concussed, disoriented, and without a memory of the incident. A security guard had found her: he thought at first she was a homeless woman, barefoot and bloody, vomiting blood and asking for an ambulance. He sought help from what the newspaper article coyly calls ‘a national private health care chain’ with offices nearby. But in the eyes of staff there, Ms Mji, barefoot, dishevelled, incoherent and black, did not look like someone who could pay. They assumed she was a vagrant, and vagrants don’t get care. Only because the security guard who had found her persisted in his efforts did an ambulance service finally respond. The news story itself soon faded from view, with no follow-up after the first indignant headlines.

Consider what is at play here — both in the incident itself, and what makes it newsworthy. Firstly, the story shows how stark the divide is between the existence of those of us who belong within the institutional grid of power and wealth at the centre of our economy, and those of us who don’t; and how harsh the consequences are. It highlights the fragility even of privilege, and how easy it is to end up on the outside. Critically, it illustrates with depressing force the continued reality of race in this country (had Ms Mji been white, would she have been so easily consigned to the streets, with only a security guard to fend for her?). But the most shameful and perverse reality is this: the fact that this story is told at all only because Ms Mji is one of ‘us’, a member of the middle class; that we can identify with her and feel the fearful thrill of thinking, that could have been me. That’s why it’s a story. Homeless people are assaulted every day, and denied care. Everyday normality does not make the news.

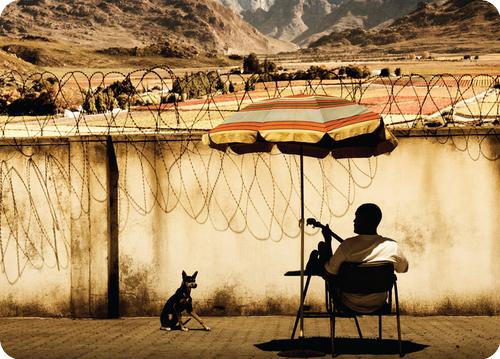

This is the society we are creating, post-Apartheid. Not only are we one of the most income-unequal societies on the planet. Not only is this inequality increasing. Not only have we created a society bisected by deeply unequal relations of power and privilege, in which the marginalized have, in truth, no rights at all. Worst of all, we live here heedlessly, comfortably. Our hearts and imaginations have been numbed.

And you can see how this kind of setup perpetuates itself, how it feeds the desire to build the walls higher, and how it drives the hungry ghosts of self-enrichment and pointless, conspicuous consumption.

So much for the obvious aspects of the story. Gubela Mji’s assault is in this respect like any story of shocking crime, a event which can function as an example to illustrate some troubling aspects of our society. But there is more to say.

So much for the obvious aspects of the story. Gubela Mji’s assault is in this respect like any story of shocking crime, a event which can function as an example to illustrate some troubling aspects of our society. But there is more to say.

For Ms Mji is not merely the subject of a story, a mute exemplar. She has a voice of her own. And by an irony rich and strange it turns out that in the past she has spoken eloquently and powerfully about these very issues. In a recent book about disability and social change, she is the author of a powerful and personal account on the exclusion and marginalization of the homeless disabled. Entitled with eerie precision ‘Disability and homelessness: a personal journey from the margins to the centre and back’ she recounts a journey of self-discovery that began when, as part of an investigation into the conditions of disabled homeless people, she lived for a week in a homeless people’s shelter. Here she had to confront her own feelings of discomfort at being in the presence of people who she had been accustomed to experience as ‘rude violent and drunk.’ Her subsequent reflections go right to the centre of the issue:

“…when I listened to someone’s life story, their problems, fantasies and struggles, something began to change. I was faced with the dilemma of wanting to hold on to something to distinguish ‘this kind of person’ from the kind of person I am. At the same time I found myself recognizing myself in their problems, fantasies and struggles…. I felt a deep concern at how far I had travelled from my rural childhood into the abstract violence of Cape Town’s urbanity, a social violence underpinning and underpinned by the abstract violence of my professional training and its attendant medical-scientific categorizations, codifications and pathologies. I was discovering in conversations with others a capacity that had been slowly eroded by the rationality and instrumentalism of my medical training and the bureaucracy and alienation of urban living”

This is the centre from which I think we can approach our question. For the power of Mji’s story is not only that by an awful irony she eventually experienced the enactment on her own body, on her own person, of the abstract institutional violence of an unequal society. It is also the precision with which she fingers her own personal complicity in that institutional violence. Wanting something to distinguish ‘this kind of person’ from the kind of person I am: Write that in letters of fire on the Union Building. Write that on every coin and Rand note in the country. This is how the divisions of an unequal society are mirrored and perpetuated in the very capacity to relate, to engage with others. And at the same time, Mji insists that there is something that can be undone; something that can be reversed. We can recover our ability to identify.

I find these reflections helpful when I consider the debates and dilemmas that shaped the conference. In my experience, I was particularly struck by what seemed to be a polarization or a disconnect between two very different ways of thinking about inequality and what could be done about it. Superficially, this disjuncture seemed to revolve around the hoary old sociological distinction between structure and agency. On the one hand, there were the researchers and analysts who emphasised the structural nature of inequality: the ways in which the domination of the economy by a highly concentrated, capital intensive corporate core undermined the basis for economic agency on the part of the poor. On the other hand there were the voluntarist accounts of community response and self-help: presentations that seemed to suggest that all that was required to resolve the problem was optimism and self-belief on the part of the poor, with a little bit of help from the State. Obviously both views had value, and spoke to part of the truth. But they seemed to exist in parallel universes, dead to the truth of each other’s arguments, and unable to see their own blind spots

Seeraj Mohammed’s presentation of labour market trends in South Africa was a very good example of the former. Mohammed’s account of the distorted development of the South African core economy, the continued domination by the minerals and energy complex, the failure of the middle class to invest in productive capacity, the centrality of credit fuelled spending and the disastrous impact of these trends on employment intensity was lucid and compelling. At the same time, what struck me most of all was the dispirited tone, and the disabling import, of this analysis. South African corporates and capitalists, Mohammed seemed to suggest, had acted selfishly to enrich themselves. Would one expect anything different? Apparently not. This was simply the way things worked in late modern capitalism. As an analysis oriented at action, it did not seem particularly helpful.

At the opposite end of the spectrum was a presentation by Lebo Ramafoko about Kwanda, a project initiated by Soul City, South Africa’s public interest messaging television programme. Charismatic and magnetic, exuding enthusiasm and confidence, Ms Ramafoko comes on like a South African version of Oprah, an impression strengthened by Soul City and Kwanda’s underlying message of emancipation through self belief and media attention. Poor local communities accessing funds for community works programmes are selected to participate in a national competition. Kwanda makes short documentaries about each community, showing their problems, highlighting the heroic efforts of local residents to address these issues; visits six months later, assessing the extent of progress made – and then invites viewers to share their advice and opinions, and to vote for their favourite projects.

It is, in other words, social development through reality television, and pretty well done television too. The clip shown at the conference portrayed, with the upbeat urgency and streetwise funky vibeyness that characterises youth television, the problems of a community called Peffertown, a peri-urban slum somewhere in the vicinity of Port Elizabeth. Dreadlocked bergies puffed at white piles, depressed community members recounted awful stories of random violence. The heroine of the story was a determined local girl called Denise, who worked to bring together community members to try to make things better. Stocky and uncompromising, with a handsome, clear-eyed gaze, she was a member of the local women’s rugby team, and she brought to her community engagement the same commitment and fierce passion she showed on the field. It was compelling viewing; a kind of strange hybrid of Andy Warhol and Che Guevara: everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes – but as a community activist.

But how realistic is all this? Lebo’s enthusiasm tempted one to believe that this is how inequality could be combated in South Africa – simply by using the connective capability of social media to create a virtual community founded on optimism and self-help. But virtual communities are evanescent, community works programmes are temporary measures that can only ameliorate the worst effects of neglect and under-investment. If the core economy fails to generate jobs, can Kwanda do more but create hype and excitement around what is, after all, band-aid?

Those are important questions. But at the same time, much would be lost if we simply dismissed Kwanda and the voices it gave space for. This is where Mji’s thoughts help us see something of value that we might miss. For Mji does not treat the loss of community feeling, the abstract violence of the withdrawal of social solidarity, as inevitable. She reminds us that capacity for it still exists. She links this capacity very much to her own cultural resources as an African woman from a rural area. But the capacity exists in us all. It is nothing more than psychological projection ; the ability and the willingness to recognise something of oneself in another.

Kwanda thus highlights two key points. Firstly, it gives an indication of how close to the surface our South African utopian imagination still lives; how real the underlying inclination of goodwill, fellow feeling and solidarity still is. And secondly, it has found a way of mobilizing this energy: it has used the power of television and media to allow parts of South Africa to have a kind of love affair with itself.

Love affairs are interesting things. The one we thought we saw is never there. Projection is, after all, illusory. But it’s a productive illusion. It can start a journey of fruitful disillusionment, a process of discovery and change. Much can be given and gained. For all its naivety and cheesy optimisim, in other words, Kwanda does something the leftist critique of structure often fails to do: it constructs a subject position from which action is still possible.

So despite its limits, Kwanda suggests the possibility of a different way of proceeding. In a way, it’s like the World Cup, where the dream of welcoming ‘the world’ allowed us to feel, for a few weeks, that the country where we would like to live really existed. Not Singapore, not Switzerland, not Sweden, but a warm hearted, vibey, ordinary country in the South. But the World Cup as an ideological project pivoted, really, on our deeply charged, troubled, relation with the North; our desire to be recognized and seen by something we call the World. It was, in other words narcissistic in the strict sense of the word; a desire to appear in a certain way in the eyes of an authoritative Other. The moment that Other disappeared, the moment we were no longer on the TV screens, the moment we could no longer see ourselves reflected in the distorting mirror of the World’s gaze, the warm glow disappearted.

My question is really about the space, in South Africa, for a discourse of civic solidarity. Can we define ourselves not in relation to the world’s gaze, not in relation to a feared interloper, but to each other? Can we find a way to meet ourselves, “at our own door, in our own mirror”? Can we act as if in some way — divided by antagonisms, to be sure, riven by hurts, burdened by memory — there is, in the end, an ‘us’? Can we imagine that?

leaving the world: avatar

‘If a man could pass thro’ Paradise in a Dream, and have a flower presented to him as a pledge that his Soul had really been there, and found that flower in his hand when he awoke — Aye, and what then?’

Samuel Taylor Coleridge

As my friend Liezel said, it’s not Woody Allen, is it? I know what she means. Not that Allen’s movies are particularly cool or cerebral these days anyway; and Emmerich knows there are plenty cruder, more clichéd films. But there are few movies on the commercial circuit that convey their clichés with such starry-eyed conviction, or where the stakes are quite as high. In a decade of CGI-dominated, predictable films, what sets Avatar apart — what makes it both worth fascinating and troubling—is the naïveté of its message, the lyricism with which it presents its utterly unconscious material, the starkness of its moral universe, and the manipulative and crude way it resolves its central contradictions. I’ve seen it twice now: each time I came prepared to see its flaws — the first time because of negative word of mouth; the second because, well, it was the second time — and each time I found myself swept along heedlessly, transported by the sheer lyricism of the moviemaking. And each time I felt flat and disappointed the next day, as if whatever had held me the night before had turned to dust.

The plot is simple: humanity is colonizing a jungle planet (actually a moon orbiting a gas giant) rather wonderfully named Pandora. The RDA corporation is strip-mining Pandora for a valuable mineral with the cringe-making name of Unobtainium. The chief obstacle in their way is not only the local environment (the atmosphere is poisonous; and the jungle is a dense, teeming Darwinian hell) but also the natives, a humanoid species called the Na’vi. They are physically formidable (they have carbon fibre in their bones, are about twelve foot tall and —the leathery Marine captain in charge of security tells us — they hard to kill); but more to the point, they are opposed to the human presence in their forest. A team of anthropologists have been trying to ‘civilize’ the Na’vi and to study them; as part of doing this (to build trust, I guess, and to avoid being killed) they don’t meet them physically: instead, they have their consciousnesses projected into vat-grown alien bodies – the Avatar of the title. The hero, Jake Sully, gets lost in the jungle in avatar form and accidentally ends up among a clan of the Na’vi called the Omaticaya. Instead of violent barbarians, he finds, they are sophisticated primitives; prelapsarian stone-agers living poetically in tune with their environment. Far from being a hell-hole, the forest is their paradise, and their spirituality is the worship of Eywa, a Gaia-like Mother Goddess embodied in a sacred tree. Forced to make a choice, Sully goes over to their side, and organizes the resistance that sends the colony – and humanity – packing.

This is all familiar territory, of course. The plot is an old science fiction standard; large sections of it (particularly Miles Quaritch, the redneck ex-Marine security man) seem to have been lifted bodily from an old Ursula Le Guin novelette called The Word for World is Forest (Quaritch is the spitting image of Le Guin’s Captain Davidson, whom she calls the most one-dimensional character she ever created). And within the frame of this story, James Cameron and John Landau have decided to bludgeon us with every noble-savage, white-man-loved-the-Chieftain’s-daughter cliché and stereotype in the book. From the word go, you know how it is going to unfold. It’s going to be Pocahontas meets Platoon. It’s going to be The Mission meets Dances with Wolves. The natives are going to be noble savages; the chief is going to be dignified and wise; his wife will be a sangoma with dreads and second sight; there will be a jealous brave who wants to kill Jake in the beginning but who becomes his comrade in the end; the aliens will be willowy and high-cheekboned; they will spout Buddhist koans; they will be wisely in touch with nature and the spirit world … but most of all, it will be a white man – oops, sorry, a human being – who awakens the natives from their rapturous trance and rescues them from the evil corporation. And so it all in fact unfolds. Moreover, all of it happens without a trace of irony, cheesy dialogue and all.

This is all familiar territory, of course. The plot is an old science fiction standard; large sections of it (particularly Miles Quaritch, the redneck ex-Marine security man) seem to have been lifted bodily from an old Ursula Le Guin novelette called The Word for World is Forest (Quaritch is the spitting image of Le Guin’s Captain Davidson, whom she calls the most one-dimensional character she ever created). And within the frame of this story, James Cameron and John Landau have decided to bludgeon us with every noble-savage, white-man-loved-the-Chieftain’s-daughter cliché and stereotype in the book. From the word go, you know how it is going to unfold. It’s going to be Pocahontas meets Platoon. It’s going to be The Mission meets Dances with Wolves. The natives are going to be noble savages; the chief is going to be dignified and wise; his wife will be a sangoma with dreads and second sight; there will be a jealous brave who wants to kill Jake in the beginning but who becomes his comrade in the end; the aliens will be willowy and high-cheekboned; they will spout Buddhist koans; they will be wisely in touch with nature and the spirit world … but most of all, it will be a white man – oops, sorry, a human being – who awakens the natives from their rapturous trance and rescues them from the evil corporation. And so it all in fact unfolds. Moreover, all of it happens without a trace of irony, cheesy dialogue and all.

And yet, and yet. And yet the movie draws you in; and at times manages to move and enthrall. What is interesting about Avatar is the way in which it manages to bring off this predictable story, manages you to suck you into its world; not in spite of but because of the clichés.

One of the ways in which it does this is through its gorgeous visual texture. In one sense, the centre of the movie is not its story, nor its actors, but the visual technology of the film itself – the hallucinatory beauty achieved through the mixing of 3D digital film making, live action and computer animation. Cameron famously waited for more than a decade for motion-capture technology to become advanced enough for his project, and it seems in this respect at least he is completely vindicated. The sophisticated animation techniques give filmmakers an imaginative reach and power not seen in film before: if nothing else, science fiction and animated films will never be the same again after Avatar. More specifically, the film works because Cameron has succeeded in translating into movement (and into three dimensions) the visual and imaginary language of decades of psychedelic SF art. For me, that was a large part of the visual pleasure of the film. As a boy who loved science fiction, one of my greatest treasures was Brian Ash’s sumptuous Visual Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, which I got, I seem to remember, for my thirteenth birthday; a book that catalogued the way in which SF art progressed from those crude early twentieth century magazine covers (Frank R Paul’s garish covers for Amazing Stories, for instance) to the psychedelic and otherworldly images invented by the airbrush artists of the 1970s. I remember hours spent gazing raptly at the strange, evocative visions of those artists : Stephen Hickman, Michael Whelan, and, above all, Roger Dean.

This, by the way is one rather interesting aspect of the film: no-one who has encountered the art of Roger Dean (many will know him from those Yes album covers) could fail to experience a shock of recognition. Those strange, spindly, dragonfly-like spaceships; the unearthly sculpted landscape, the flying lizard creatures, the flying islands – all of these seem not just to be quotes from Roger Dean, but straight cribs. Yet Dean does not seem to get any recognition in the credits. As one fan site notes, when life imitates art, it’s one thing, but when art imitates art, it’s another.

But more is going on here than visual wizardry and artistic plagiarism. In a way, what the movie does visually is to split the world into two realms: the technological world of the Corporation, all steel and bulkheads, shot in grim, greyed-out colours, and the magical world of the jungle, which is presented as a fairyland. And I mean that literally. In a sense, the visual disjuncture in the movie marks (or perhaps hides) a genre disjuncture, for it seems to me that in emotional, genre and mythographic terms the jungle aspects of the movie are not science fiction at all, but fantasy. In entering the world of the jungle, Jake Sully enters the realm of Faerie – not another physical realm but another world entirely. This is particularly obvious in the sequences where Jake first arrives at Home Tree, the natives’ city-in-the-branches. Butterflies all round, glowing mushrooms, silver leaves, gargantuan trees with buttresses spiraling into the light: this is not Pandora, this is Lothlórien; and the aliens are not humanoids from another planet, they are Tolkien’s Elves, imbued with all the powers and qualities proper to them.

Lothlorien. Original image at http://www.lilithschilde.com/LOTR/lothlorien.jpg

Middle-Earth, of course, is an interesting place. It serves many ideological and psychological functions and holds many projections; but one of the most important achievements of Tolkien’s mythos is how it connected myth and archetype with, on the one hand, a distinctively late twentieth-century environmental imaginary (remember this about Gandalf: he was always the only wizard who really understood trees) and, on the other hand, a wistful, fey, elegiac romanticism. At the heart of this romanticism, I always think, is a longing for lost innocence, for youth departed; a yearning for the mythical memory of the time that magic was real, when we were one with the world, before we ate the fruit of the knowledge of good and evil.

This is the psychic and symbolic terrain occupied by Avatar; this is what gives it its emotional and psychological charge: its seduction lies in the starry-eyed conviction, the unblinking naïveté, with which it evokes the the possibility of Paradise, of being at one with the world, of living before the Fall. Nowhere is this fey, wild magic more passionately conveyed than in the long sequence where Jake Sully, as part of his rite of passage into Omaticaya manhood, has to capture, vanquish, “imprint” , and ride one of the flying lizards that live in the floating islands in the sky above the mother tree. Again, we are in solid science fiction cliché territory ( in this case, most obviously, the movie evokes Anne McAffrey’s Dragonriders of Pern books, a series of fantasy bodice-rippers where dragon-riders form a similar life-long bond with their mounts). But the sequence is ravishingly filmed. This is where the Roger Dean imagery really comes into its own. The camera gives us scene after unreal scene of unearthly beauty: the warriors swarming up a steep hill, snagging a passing root-tendril from a floating island, climbing up into the sky… each shot tops the previous one in eldritch weirdness and picturesque unreality. And the animation makes it all seem more real than real, bringing home on the screen the romance of the floating, flying world, the brutal, scaly weight of those lizard bodies, and the sheer thrill of flight. We understand, with a wrench, what this means for Sully, who in real life is wheelchair-bound: his rite of passage seems to have ripped him loose from reality altogether: an ex- Marine with a shattered body, locked in a metal pod connecting him to an artificial avatar, he is transported into this astonishing wonderland, scary and beautiful, in which anything can happen. And we the audience are taken along. Suddenly the plot is forgotten as we watch the lizard riders fly free through the sky; diving down sheer cliffs like so many BASE jumpers, lost in the exultation of flight. To my mind it is one of the most visually intense – and intensely lyrical – sequences cinema has given us in a long time.

But where to take all this? Just as the film’s effectiveness lies in its power to evoke the dream of life before the fall, it is in the context of its evocation of this dream that the film’s ultimate immaturity, and its betrayal of its narrative responsibilities, needs to be grasped. Having created this dichotomy – between the broken world of humanity and the whole one of the aliens, between industrial, technological life and the magical one – the film is posed with the challenge of figuring out how to resolve it. How indeed?

One way is the way charted by Tolkien, at least in the Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit. As you will remember, in both these stories we are continually being reminded that the time of magic is ending. The elves are leaving Middle-Earth; and though Frodo can go with them, sailing to the Western Shores, the last words in the book belong not to Frodo but to Sam. Sam does not get to remain in Fairyland; he has to return home to Rose and the Shire (a Shire which, though it has been spared Pandora-like mining and Industrial Revolution, is now increasingly part of the real world); here Sam will have to labour in his garden and take up adult responsibilities, his feet on the ground. ‘Well I am back,’ he says to Rose, turning his back on the Elvish world; and I have always thought it is a well-nigh perfect ending.

Philip Pullman makes the same point, in a different way, in the Dark Materials trilogy – not only in Will and Lyra’s courageous decision to close the door between the worlds, but also in Pullman’s intellectual debt to Kleists’s essay on the Marionette Theatre. In this essay, Kleist argues that the state of grace embodied in lost youthful innocence cannot and should not be regained. For Kleist, and for Pullman, there is no way back. We are thinking beings now, separate from the world. An angel with a burning sword guards the gate of Paradise. Re-attaining grace requires us to build the Republic of Heaven in this world: we have to go forward, use what we learned from the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge, forsake innocence, take up adult consciousness.

But the film does not follow this path. It could have done so: we can imagine a movie in which Jake leaves Pandora in its unspoilt wildness, taking the Corporation with him. Or the film could give us the real ending, the outcome we secretly know is inevitable: the World Tree killed, the aliens enslaved and alcoholic, Pandora terraformed, the jungle destroyed or preserved only in isolated natural parks. But this is not the story the film tells; it dares not tell it like this. No: somehow the garden of Eden must triumph… no, more; it must triumph and maintain its original innocence. That is what infantile desire (read: Hollywood convention) requires.

But the problem is that this cannot be achieved without breaking the unwritten rules of satisfying and true fiction. For a fictional victory to be psychologically true, for it to be resonant and satisfying, something must be lost. Frodo has to lose his living connection to Middle-Earth; Will has to lose Lyra; Ged has to give up his power. If nothing is lost, the prize offered by the story will be a hollow clanging shell. And so the movie descends into bathos: a pitched, armed confrontation between the Omaticaya and the forces of the Corporation. With this, despite all the visual wizardry, the movie loses its magic. We are back watching some kind of post-Nam jungle firefight. The point is not only that the Hollywood plot mechanics here are grimly familiar and utterly predictable, right down to that last physical battle between Sully, Neytiri and Quaritch (how many Hollywood movies right now are ending with one key figure fighting a desperate battle in a disintegrating exoskeleton? I count Iron Man, I count District 9, I count Avatar… ) It is that, try as we might, we cannot ignore the uncomfortable fact that Sully prevails only by turning the Na’vi into that which they oppose. One horrible jarring note is struck when we realize that somehow (it is never explained how) the Omaticaya appear to have acquired a lot of modern day electronic battle-comms gear, whispering tersely to one another over earbud headphones and microphones. Another is when the wild beasts of the jungle rise up together against mechanized invasion. This was not supposed to happen: As Neytiri explained earlier, Pandora’s mother-goddess looks after the balance of life and death itself; praying to her for help in an actual battle meant to go one way or the other is to misunderstand what she is about. The creatures of the wild are not supposed to be recruitable for tactical military maneuvres. But this is a Hollywood movie. Paradise may be Paradise, and the Balance of Life and Death is all very well, but if Nature really knew what was good for her, she would be revealed to be at heart American, viz. able to use organized aggression in the defense of Freedom.

And so it goes. The movie supposedly ends in triumph, but there is something anticlimactic about it, with the Earthlings sent packing like so many British colonialists after a particularly successful Boston Tea Party. It all feels contrived and dishonest. And the heart of the dishonesty lies in the film’s refusal to contemplate the possibility of waking up, of coming back from Faerieland.

Waking up, of course, is a difficult challenge. As Jungian analyst Julian Davis often liked to remark (apropos, I think, of the myth of Orpheus), it is easy to enter the Underworld; the hard thing is to bring back into the real world the treasures and the wisdom you found there. As I have argued elsewhere, Chihiro manages it in Spirited Away, going back into teenage life with her unsatisfactory parents, but having established her own connection with the River Spirit. The eponymous heroine in Coraline does not: she abandons the magical world, closing the trapdoor on the possibilities of yearning and desire. Jake Scully, in contrast, follows the path of Ofelia in Pan’s Labyrinth: Ofelia, you remember, chooses not to go back to the real adult world, opting instead to live in Faerie forever. Similarly the real climax, the final punchline of the movie is not the political resolution of the humans leaving Pandora: it is the last shot, in which Jake’s Avatar’s eyes open, signifying that he has died in his human body, and can live transferred to this artificial one, in this fantasyland, forever.

What is this saying about the culture that made it? Two things stand out. Firstly, and most obviously, like Dances with Wolves and The Mission, the film’s psychological immaturity reflects and enables an underlying political dishonesty. It enables an American, first world audience both to have its cake and eat it. On the surface the film seems to critique present day American imperialism (the head of the mining operation, Parker Selfridge, is a smug, golf-playing, chubby Bush lookalike, and the beefy Quaritch at times appears to spout verbatim Bushisms) but it never undermines the underlying dichotomies and splits that emanate from the colonialist, imperialist viewpoint. The most obvious and juvenile manifestation of it is Scully’s role as rescuer, and the movies cheesiest, falsest note — worse even than that Unobtainium, worse than the battle radio — is the moment when Scully leads the Na’vi in the preparations for battle. ‘This is our land!’ he cries; and the appalling dishonesty of that moment is the dark mirror of the breathless yearning of the dragon flight sequence. Less obvious, but as insidious, is the movie’s shameless exploitation of the noble-savage myth. A lot of what is queasy-making about Avatar is what is queasy-making about a certain kind of alternative modern consciousness in the real world: I am speaking here of the creepy ‘new age’ ideology that deals with an awareness of the unsustainability and violence of modern, industrial life by making ‘primitive people’ and ‘first nations’ the screens on which all our own spiritual and political needs are projected. Queasy-making because of the detachment from real life this split requires and enables: its refusal to acknowledge the reality of our existence in this broken, post-industrial world and its failure to recognise the physical and political reality of the ‘others’ upon which these golden fantasies are projected. (This is what made District 9 so fascinating: in all its evocation of xenophobia and racism, it is a much more honest attempt to imagine the encounter with the alien ‘Other’).

The first Avatar: Hiro Protagonist, in Snow Crash. Image by nClaire, posted here: http://nclaire.deviantart.com/art/Snow-Crash-Hiro-Protagonist-132297300

The second thing is this: linked to this detachment is the way the film evokes the power and centrality of notions of virtuality in modern imaginative life. The film’s title and central device is crucial here. Jake Scully’s avatar, at least, is flesh and blood (and, presumably, carbon-fibre strengthened bone), and is, we are told, worth millions. But in the real America, avatars are a dime a dozen. These days, ‘avatar’ does not stand for a divine manifestation; instead it is a word for a few lines of code, a pictogram with which you can denote yourself – and thereby assume a whole new persona — when interacting with others on the Internet. This usage of the word originally comes from Neal Stephenson’s novel Snow Crash, where people use avatars to inhabit an imaginary virtual universe called the Metaverse. Ten years after Stephenson’s novel, the Metaverse has attained actuality, for example in constructs like Linden’s Second Life, where you (or you avatar) can transport your whole social life into a virtual world, interacting with others, having (virtual) sex, and (crucially) buying property. It all sounds rather awful and boring; but at least it is not real. Reality… reality we don’t want. Not in our dreams.

And this is what Avatar seems to promise, with its gorgeous visual textures, its sumptuous three-D, its notion of projecting your consciousness into another body, another world. It seems to be a metaphor for the experience of cinema itself, for what it can promise. The tagline for the movie is evocative, double edged. Enter the World, it says. But what it really means is, Leave it. The real world is too broken. Industrial civilization may be raping the planet, but dealing concretely and practically with our accountability for our impact in the real world is asking too much from us. Let us rather sleep. Let us depart into the virtual, disembodied world. Let us dream.

Walking out the Cinema Nouveau after seeing Steven Soderbergh’s new movie The Informant!, which tells the true- life story of Mark Whitacre and his role in the investigation into price fixing at ADM, I was suddenly aware of a crawling, itching sensation of dread. All at once, fearful thoughts about the past week at work came crowding in — struggles with financial reports to donors, attempts to develop new funding proposals, my own career plans and decisions — and it all seemed too much: doomed to fail, puny struggles in the uncaring eyes of the Powers that Be. In the car on the way home, my father — usually not someone given to complaint — started telling me about his hassles with his pension company. The date stamp on his ‘life certificate’, which he has to send them every year to keep the payments coming, had been wrong, and for weeks now he had been on the phone to faceless voices at the call centre, trying to convince the company he was still alive. I found it an unsettling story, an unwelcome reminder of how powerless we really are — we, the supposedly valued consumers at the centre of our present-day culture of money and consumption — when we lose our foothold in the distributed systems of process and information that undergird our lives.

It reminded me of a few lines from Lao Tsu which have been pinging around in my head for some time now. We don’t know who ‘Lao Tsu’ was. The name (Laozi, in the new orthography) apparently means simply ‘the old master’; ‘he’ may in any case not have been just one person: there might have been a whole line of old men (and women, I am sure). But the poems collected in the Tao te Ching, obscure and evocative, often seem uncannily resonant of lessons to be learned today. When the Way is lost, it says in Chapter 38, there is always goodness. When goodness is lost, there is love or kindness. When kindness is lost, there’s justice. And when justice is lost … well, then you’ve got HR and Customer Relations Management. Well, that’s not the way he put it – the text says ritual – but you get my drift: we’re in trouble. In my current job as manager in a small university-based research unit, I have been much concerned with thinking about the systems and processes that can make working life either rewarding, empowering, enjoyable, or a living hell. (And those worlds, let me tell you, can be a hair’s breadth apart.) Systems are important, all right, and so are procedures, and so are policies aimed at addressing gender discrimination, or racialized exclusion, or unfairness. But the more I do this work, the more I am convinced that it is the integrity of our relationships with one another and ourselves, the quality of attention that we can bring into the workplace that really makes the difference. I am not sure whether a policy research organization operating in today’s divided, disconnected world can ever manifest the Way that ‘Lao Tse spoke about. Even “Goodness” (real virtue, which does not seek to be recognised as such) seems improbable. But Kindness seems to me to be a minimum requirement, and you’d be surprised how hard that is. Well, not really. You are also a subject of present-day neoliberal capitalist bureaucracy — who isn’t? — so unless you are delusional, you’ve felt it too: that the rules and systems that regulate our lives in the present day world are not only impersonal and unfeeling, but dangerous too, and that underneath their rationality there is something deeply disconnected. Ritual and empty form, they rule our lives, and so, indeed we’re truly lost.

It reminded me of a few lines from Lao Tsu which have been pinging around in my head for some time now. We don’t know who ‘Lao Tsu’ was. The name (Laozi, in the new orthography) apparently means simply ‘the old master’; ‘he’ may in any case not have been just one person: there might have been a whole line of old men (and women, I am sure). But the poems collected in the Tao te Ching, obscure and evocative, often seem uncannily resonant of lessons to be learned today. When the Way is lost, it says in Chapter 38, there is always goodness. When goodness is lost, there is love or kindness. When kindness is lost, there’s justice. And when justice is lost … well, then you’ve got HR and Customer Relations Management. Well, that’s not the way he put it – the text says ritual – but you get my drift: we’re in trouble. In my current job as manager in a small university-based research unit, I have been much concerned with thinking about the systems and processes that can make working life either rewarding, empowering, enjoyable, or a living hell. (And those worlds, let me tell you, can be a hair’s breadth apart.) Systems are important, all right, and so are procedures, and so are policies aimed at addressing gender discrimination, or racialized exclusion, or unfairness. But the more I do this work, the more I am convinced that it is the integrity of our relationships with one another and ourselves, the quality of attention that we can bring into the workplace that really makes the difference. I am not sure whether a policy research organization operating in today’s divided, disconnected world can ever manifest the Way that ‘Lao Tse spoke about. Even “Goodness” (real virtue, which does not seek to be recognised as such) seems improbable. But Kindness seems to me to be a minimum requirement, and you’d be surprised how hard that is. Well, not really. You are also a subject of present-day neoliberal capitalist bureaucracy — who isn’t? — so unless you are delusional, you’ve felt it too: that the rules and systems that regulate our lives in the present day world are not only impersonal and unfeeling, but dangerous too, and that underneath their rationality there is something deeply disconnected. Ritual and empty form, they rule our lives, and so, indeed we’re truly lost.