imagine

The most thought-provoking words spoken at the Boksburg Inequality Conference that we and our partners hosted in Gauteng last month were uttered right at the end, almost as an aside, by the conference’s closing speaker, Neva Makgetla. Reminiscing about her days studying philosophy in East Germany (as it then was), she said that what had struck her was that that the original motivation of those who had tried to create a socialist society – the promise that they had struggled to fulfil – was that socialism would enable a change in the quality of human relationships. But in practice, trying to make a society work, they decided to focus on material things. Money, social services, schools. Perhaps here in South Africa, she said, something similar had happened. The struggle against Apartheid was linked to a dream of what could be possible in the new society, the possibility of something qualitatively different from the fear-filled disconnections constituted by Apartheid. But a country had to be run, programmes designed. And this is what we’re left with, she implied: BEE and social grants.

It was a sobering comment, for it made me think that perhaps we, the organizers of the conference, had somewhat lost sight of our topic. The conference had been organized in order to try to put the issue of inequality more squarely on the South African policy agenda. All too often, discussions about social issues in South Africa proceed as if poverty is a residual matter, the result of some people somehow being left out of economic growth: as if all that is required is to provide them with the assistance and opportunities that are needed to raise their incomes (the current reach-for-my-revolver term is to ‘graduate’ them) above some (usually unspecified) poverty line.

We wanted to challenge those assumptions. We wanted to argue that the central and most urgent issue facing South Africa is not poverty but inequality; and that in South Africa, poverty and inequality were structural. That our economy, while generating wealth for a few, is also a poverty machine, perpetuating and exacerbating steep and deeply rooted inequalities that threaten the basis of social stability and growth. We wanted to use the conference to cast a spotlight on this trend: to ask what kind of society was emerging, and to invite participants to explore what alternatives were possible. Could we imagine a different society, with different values? What would such a society look like?

I was reminded of that aim on the first morning of the conference, when the organizing committee met in the Birchwood’s faux-Italian coffee shop to discuss the start of the proceedings. The conference would be opened by Deputy President Kgalema Mothlante (on DVD, the man himself being required at the ANC NGC in Durban) – after which there would be a recital by performance poet Flo. Flo was there, a shy, burly man with a ready smile. We chatted with him about his plans for his performance, and asked him what he thought he would recite. What would his poems be about? He thought for a moment and said, oh, social issues. And love. There was a moment’s embarrassed silence. Love? Well, I thought, perhaps that was precisely what we were here to talk about. All my relations, and the world they exist in.

I was reminded of that aim on the first morning of the conference, when the organizing committee met in the Birchwood’s faux-Italian coffee shop to discuss the start of the proceedings. The conference would be opened by Deputy President Kgalema Mothlante (on DVD, the man himself being required at the ANC NGC in Durban) – after which there would be a recital by performance poet Flo. Flo was there, a shy, burly man with a ready smile. We chatted with him about his plans for his performance, and asked him what he thought he would recite. What would his poems be about? He thought for a moment and said, oh, social issues. And love. There was a moment’s embarrassed silence. Love? Well, I thought, perhaps that was precisely what we were here to talk about. All my relations, and the world they exist in.

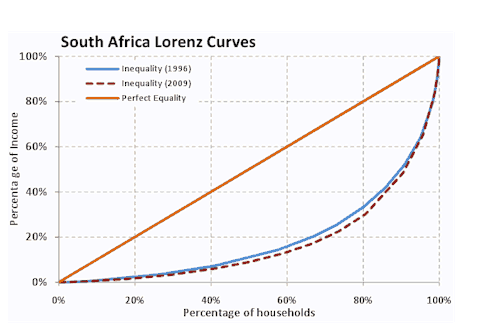

In the event, Flo’s poems were moving, thought provoking and disarming, and did their part to break the ice and get things moving. But pretty soon his words were forgotten, and the participants went ahead, doing what people do at poverty and inequality conferences: considering Lorentz curves, analysing political systems, discussing job creation and rural development. And at that level the conference was, as conferences go, successful. Makgetla’s presentation showed clearly how considering poverty on its own, in isolation, leads to narrow policies focussing merely on particular marginalized groups, while a focus on inequality leads to much more searching questions on the need for social transformation. Other presentations illuminated various aspects of the structural roots of inequality – the legacy of Apartheid, the failure to embark on an employment-intensive growth path, the continued dominance of capital- and energy intensive sectors, and the enormous levels of concentration and centralized corporate power in the formal economy. And there were searching discussions about particular policies and instruments – social protection, small farmer development, community work programmes – that could address these problems.

But in the end, listening to Makgetla’s closing words, I realized that we too, by concentrating mostly on the material, monetary aspects of inequality and poverty, had missed the opportunity to think about the nature and quality of social relations. Sure, there were some good analyses on gender and power relations in labour markets, and on the politics of pro-poor development. But most of our discussions had focussed on material resources, on institutions, on money and social goods. Granted, this was not a poetry conference. We were social scientists, government policymakers, development practitioners, community organizers; not philosophers or novelists. We talked about the things we knew. But what about the more elusive issues? What about thinking about the kind of society that was emerging at more moral, existential or ethical level? What about the obligations and bonds between citizens? What about identity? What about the cordoned heart? What about the structures of feeling, non-feeling and disconnection created by how power, money and fear move in this harsh land? In my own presentation at the conference, I had closed by asking what the scope was for a different project – not technical poverty management, or adversarial populist struggle, but on civic solidarity. Stirring words. But how does one even start thinking about how such a politics might look? Somehow, it is hard to thinking about this issue without getting lost in clichés and in potted thinking.

Hence this essay. My concern today is utopia; or rather, how to find a space for utopian thinking that can have grip or traction in this world. This blog is in the first place concerned with the myths we live by: the lenses through which we look; the resources at our disposal when we try to see what is found there, to imagine what it means, and to dream what’s possible. And in the case of thinking about ‘equality,’ about social relations, it’s hard to find a way of speaking that does not cause us immediately to get lost in prefabricated stories. Analyses of monetary inequality are all very well, but they are mistaken when they confuse the smooth curves that map the distribution of resources in society for social inequality which, as Charles Tilly has pointed out, is a thing of sharp distinctions, pregnant hierarchies, small differences with huge consequences: the difference between black and white, between master and slave, boss and employee. (Or to cite an example close to home for me, permanent university staff and talented researchers still on short-time contracts after 10 years of hard work.) The economists’ conception of perfect equality (everyone has the same income) is useful as a mathematical hypothesis, but it kind of misses the point. Utopian dreams of brother / sisterhood and inequality are deeply compelling (I still get choked up by that Lennon song…) but they’re closed, dislocated fantasies, shaped more by infantile longings for things not to be real than by a gritty assessment of what’s possible. And don’t talk to me about the South African variant: the way talk about racial relations shades so soon into sentimental fantasies about reconciliation, colour-blindness, impossible projects of reparation or essentialist lamentations about how terrible it is to be white. It can be fun for those who do it, but it does not offer much help for those who have to learn to get along, accomplish tasks, feed kids and run businesses in a world in which difference and antagonism are irreducible, real, and maybe even valuable.

So what can we imagine? What can and should we want? I don’t think I have answers. What I have is some disconnected dots; and my guess is that thinking about them may not give me a route, but at least it may help us get a sense of how the map looks, and the lie of the land.

So bear with my meandering argument here. A good place is to start with where we are. Specifically, the Rosmead shopping centre, in Rosmead Road, Kenilworth, where academic Gubela Mji, head of the Centre for Rehabilitation Studies in the Faculty of Health at the University of Stellenbosch Health, was brutally assaulted in September of this year. No-one knows what happened: Ms Mji was stabbed and had received blows to her head severe enough to leave her concussed, disoriented, and without a memory of the incident. A security guard had found her: he thought at first she was a homeless woman, barefoot and bloody, vomiting blood and asking for an ambulance. He sought help from what the newspaper article coyly calls ‘a national private health care chain’ with offices nearby. But in the eyes of staff there, Ms Mji, barefoot, dishevelled, incoherent and black, did not look like someone who could pay. They assumed she was a vagrant, and vagrants don’t get care. Only because the security guard who had found her persisted in his efforts did an ambulance service finally respond. The news story itself soon faded from view, with no follow-up after the first indignant headlines.

Consider what is at play here — both in the incident itself, and what makes it newsworthy. Firstly, the story shows how stark the divide is between the existence of those of us who belong within the institutional grid of power and wealth at the centre of our economy, and those of us who don’t; and how harsh the consequences are. It highlights the fragility even of privilege, and how easy it is to end up on the outside. Critically, it illustrates with depressing force the continued reality of race in this country (had Ms Mji been white, would she have been so easily consigned to the streets, with only a security guard to fend for her?). But the most shameful and perverse reality is this: the fact that this story is told at all only because Ms Mji is one of ‘us’, a member of the middle class; that we can identify with her and feel the fearful thrill of thinking, that could have been me. That’s why it’s a story. Homeless people are assaulted every day, and denied care. Everyday normality does not make the news.

This is the society we are creating, post-Apartheid. Not only are we one of the most income-unequal societies on the planet. Not only is this inequality increasing. Not only have we created a society bisected by deeply unequal relations of power and privilege, in which the marginalized have, in truth, no rights at all. Worst of all, we live here heedlessly, comfortably. Our hearts and imaginations have been numbed.

And you can see how this kind of setup perpetuates itself, how it feeds the desire to build the walls higher, and how it drives the hungry ghosts of self-enrichment and pointless, conspicuous consumption.

So much for the obvious aspects of the story. Gubela Mji’s assault is in this respect like any story of shocking crime, a event which can function as an example to illustrate some troubling aspects of our society. But there is more to say.

So much for the obvious aspects of the story. Gubela Mji’s assault is in this respect like any story of shocking crime, a event which can function as an example to illustrate some troubling aspects of our society. But there is more to say.

For Ms Mji is not merely the subject of a story, a mute exemplar. She has a voice of her own. And by an irony rich and strange it turns out that in the past she has spoken eloquently and powerfully about these very issues. In a recent book about disability and social change, she is the author of a powerful and personal account on the exclusion and marginalization of the homeless disabled. Entitled with eerie precision ‘Disability and homelessness: a personal journey from the margins to the centre and back’ she recounts a journey of self-discovery that began when, as part of an investigation into the conditions of disabled homeless people, she lived for a week in a homeless people’s shelter. Here she had to confront her own feelings of discomfort at being in the presence of people who she had been accustomed to experience as ‘rude violent and drunk.’ Her subsequent reflections go right to the centre of the issue:

“…when I listened to someone’s life story, their problems, fantasies and struggles, something began to change. I was faced with the dilemma of wanting to hold on to something to distinguish ‘this kind of person’ from the kind of person I am. At the same time I found myself recognizing myself in their problems, fantasies and struggles…. I felt a deep concern at how far I had travelled from my rural childhood into the abstract violence of Cape Town’s urbanity, a social violence underpinning and underpinned by the abstract violence of my professional training and its attendant medical-scientific categorizations, codifications and pathologies. I was discovering in conversations with others a capacity that had been slowly eroded by the rationality and instrumentalism of my medical training and the bureaucracy and alienation of urban living”

This is the centre from which I think we can approach our question. For the power of Mji’s story is not only that by an awful irony she eventually experienced the enactment on her own body, on her own person, of the abstract institutional violence of an unequal society. It is also the precision with which she fingers her own personal complicity in that institutional violence. Wanting something to distinguish ‘this kind of person’ from the kind of person I am: Write that in letters of fire on the Union Building. Write that on every coin and Rand note in the country. This is how the divisions of an unequal society are mirrored and perpetuated in the very capacity to relate, to engage with others. And at the same time, Mji insists that there is something that can be undone; something that can be reversed. We can recover our ability to identify.

I find these reflections helpful when I consider the debates and dilemmas that shaped the conference. In my experience, I was particularly struck by what seemed to be a polarization or a disconnect between two very different ways of thinking about inequality and what could be done about it. Superficially, this disjuncture seemed to revolve around the hoary old sociological distinction between structure and agency. On the one hand, there were the researchers and analysts who emphasised the structural nature of inequality: the ways in which the domination of the economy by a highly concentrated, capital intensive corporate core undermined the basis for economic agency on the part of the poor. On the other hand there were the voluntarist accounts of community response and self-help: presentations that seemed to suggest that all that was required to resolve the problem was optimism and self-belief on the part of the poor, with a little bit of help from the State. Obviously both views had value, and spoke to part of the truth. But they seemed to exist in parallel universes, dead to the truth of each other’s arguments, and unable to see their own blind spots

Seeraj Mohammed’s presentation of labour market trends in South Africa was a very good example of the former. Mohammed’s account of the distorted development of the South African core economy, the continued domination by the minerals and energy complex, the failure of the middle class to invest in productive capacity, the centrality of credit fuelled spending and the disastrous impact of these trends on employment intensity was lucid and compelling. At the same time, what struck me most of all was the dispirited tone, and the disabling import, of this analysis. South African corporates and capitalists, Mohammed seemed to suggest, had acted selfishly to enrich themselves. Would one expect anything different? Apparently not. This was simply the way things worked in late modern capitalism. As an analysis oriented at action, it did not seem particularly helpful.

At the opposite end of the spectrum was a presentation by Lebo Ramafoko about Kwanda, a project initiated by Soul City, South Africa’s public interest messaging television programme. Charismatic and magnetic, exuding enthusiasm and confidence, Ms Ramafoko comes on like a South African version of Oprah, an impression strengthened by Soul City and Kwanda’s underlying message of emancipation through self belief and media attention. Poor local communities accessing funds for community works programmes are selected to participate in a national competition. Kwanda makes short documentaries about each community, showing their problems, highlighting the heroic efforts of local residents to address these issues; visits six months later, assessing the extent of progress made – and then invites viewers to share their advice and opinions, and to vote for their favourite projects.

It is, in other words, social development through reality television, and pretty well done television too. The clip shown at the conference portrayed, with the upbeat urgency and streetwise funky vibeyness that characterises youth television, the problems of a community called Peffertown, a peri-urban slum somewhere in the vicinity of Port Elizabeth. Dreadlocked bergies puffed at white piles, depressed community members recounted awful stories of random violence. The heroine of the story was a determined local girl called Denise, who worked to bring together community members to try to make things better. Stocky and uncompromising, with a handsome, clear-eyed gaze, she was a member of the local women’s rugby team, and she brought to her community engagement the same commitment and fierce passion she showed on the field. It was compelling viewing; a kind of strange hybrid of Andy Warhol and Che Guevara: everyone will be famous for fifteen minutes – but as a community activist.

But how realistic is all this? Lebo’s enthusiasm tempted one to believe that this is how inequality could be combated in South Africa – simply by using the connective capability of social media to create a virtual community founded on optimism and self-help. But virtual communities are evanescent, community works programmes are temporary measures that can only ameliorate the worst effects of neglect and under-investment. If the core economy fails to generate jobs, can Kwanda do more but create hype and excitement around what is, after all, band-aid?

Those are important questions. But at the same time, much would be lost if we simply dismissed Kwanda and the voices it gave space for. This is where Mji’s thoughts help us see something of value that we might miss. For Mji does not treat the loss of community feeling, the abstract violence of the withdrawal of social solidarity, as inevitable. She reminds us that capacity for it still exists. She links this capacity very much to her own cultural resources as an African woman from a rural area. But the capacity exists in us all. It is nothing more than psychological projection ; the ability and the willingness to recognise something of oneself in another.

Kwanda thus highlights two key points. Firstly, it gives an indication of how close to the surface our South African utopian imagination still lives; how real the underlying inclination of goodwill, fellow feeling and solidarity still is. And secondly, it has found a way of mobilizing this energy: it has used the power of television and media to allow parts of South Africa to have a kind of love affair with itself.

Love affairs are interesting things. The one we thought we saw is never there. Projection is, after all, illusory. But it’s a productive illusion. It can start a journey of fruitful disillusionment, a process of discovery and change. Much can be given and gained. For all its naivety and cheesy optimisim, in other words, Kwanda does something the leftist critique of structure often fails to do: it constructs a subject position from which action is still possible.

So despite its limits, Kwanda suggests the possibility of a different way of proceeding. In a way, it’s like the World Cup, where the dream of welcoming ‘the world’ allowed us to feel, for a few weeks, that the country where we would like to live really existed. Not Singapore, not Switzerland, not Sweden, but a warm hearted, vibey, ordinary country in the South. But the World Cup as an ideological project pivoted, really, on our deeply charged, troubled, relation with the North; our desire to be recognized and seen by something we call the World. It was, in other words narcissistic in the strict sense of the word; a desire to appear in a certain way in the eyes of an authoritative Other. The moment that Other disappeared, the moment we were no longer on the TV screens, the moment we could no longer see ourselves reflected in the distorting mirror of the World’s gaze, the warm glow disappearted.

My question is really about the space, in South Africa, for a discourse of civic solidarity. Can we define ourselves not in relation to the world’s gaze, not in relation to a feared interloper, but to each other? Can we find a way to meet ourselves, “at our own door, in our own mirror”? Can we act as if in some way — divided by antagonisms, to be sure, riven by hurts, burdened by memory — there is, in the end, an ‘us’? Can we imagine that?

Phew, its been a while, and its been well worth the wait. I need to digest this before and if I find the desire/need to respond something so eloquently argued, but wanted to say thank you nonetheles…

wonderful

Hi Andries,

Just wanted to let you know that I really enjoy your blog. I discovered it right after your Avatar post in January and am so glad to find that I didn’t completely miss the party! I’ll keep my fingers crossed in hopes of seeing more film essays in the near (or distant) future… Any chance you plan to write on Inception? I’d be fascinated to hear your take. In any case, thank you for taking time to share your wonderful and always thought-provoking insights…

Take care,

Eremi

Thanks for your kind comments. Yes, I hope some film essays will be on the way. Although most probably not about Inception, which I hated. I thought it was contrived and boring, and I walked out after an hour. Maybe there was a twist ending which redeems it all (he dreamed it all?) but I thought it was a shockingly bad film for such a talented director. Perhaps the new Coen brothers movie will be worth reviewing…

Thank you for yet another post which illuminates both my nation and my self. Your discussion of Gubela Mji resonates with me deeply, especially this line:

“Our hearts and imaginations have been numbed.”

I realised recently that it’s been years since I was moved to tears by anything – a book, a film, a news story, another person. It really bothered me, that fear that I have become calloused. But I’ve just spent a week in the US learning the art of facilitating storytelling, by the end of which the gates were unlocked and I was weeping freely. I’m more than ever convinced that sharing our own most deeply felt personal stories is one of the most transformative ways we can connect with each other — and that denying people their own stories is a primary kind of violence. In my utopia, we all listen to each other a lot.

Hi Andries,

“We wanted to argue that the central and most urgent issue facing South Africa is not poverty but inequality.”

I’d be interested to hear if this was ever argued, and what arguments were put forward to support this claim?

As John Rawls (and the demise of Communism/Socialism?) have shown in the past, surely a society can happily condone (and even encourage) social and economic inequalities, as long as they are to the greatest benefit of the least advantaged members of society?

In simple terms, inequality is needed to grow the size of the cake and (through a progressive tax system, for example) improve the position of the poor.

Your thoughts?

Hi Theo,

The argument was made several times, among others (as I point out) by Neva Makgetla, who argued that from a social justice point of view a focus on poverty is much less conducive to equitable and transformative policy interventions than a focus on inequality. This is particularly so given the narrow definitions of poverty that typically hold sway in mainstream approaches: these define poverty in terms of a monetary poverty line, which is usually set at very low levels. Combating poverty then becomes a matter of lifting the incomes of ‘the poor’, as they are called, above this line. Thus the problem can be ‘solved’ without fundamental social injustice being addressed.

This, of course, is if you assume deep inequality is incompatible with social justice. I do indeed assume that. And I don’t think Rawls would disagree. I am not sure I read you correctly, but it does look to me as if you fundamentally misunderstand what Rawls was doing. His argument is not directed at showing that inequality is tolerable. Rather, his work is an attempt to deduce a theory of justice from first principles – principles that everyone could agree on. His postulation is that all reasonable people would agree that it would be fair to have a society in which the least advantaged people would have the best of all possible deals. South Africa manifestly fails the test of Rawlsian fairness.There is no way that inequality in South Africa can be described as being to ‘the greatest benefit to the least advantaged members of society.’ I don’t think even Anne Bernstein would suggest that! Also, inequality in South Africa is linked to low levels of social mobility, which violates Rawls’s stipulation that inequality, where it exists, must be attached to positions and offices that are open to all.

In any case, I don’t think Rawls is very useful here. Rawls was trying to reinvent social contract theory for the modern age. We at the conference were dealing with the very concrete case of South Africa – one in which the corrosive effects of inequality is affecting the cohesion of the society as a whole and threatening political stability. One of the most insightful recent takes on this is the report that Anthony Altbeker recently wrote for the Centre for the Study of Violence and Reconciliation, in which he makes a powerful case that South Africa’s high levels of violent crime are directly linked to the structural nature of inequality. We’re not behind a Rawlsian veil of ignorance here: we are in a society in which high levels of inequality are threatening the values of our democracy.

It is, by the way, highly debatable that inequality is needed to grow the size of the cake. It could be that moderate levels of inequality are an inevitable consequence of a dynamic and growing modern society. But many economists would also argue that beyond a certain level, inequality starts being growth-constraining. In South Africa, the fact that we have such a small middle class, and such a poor working class, is certainly a constraint on growth.

Thanks Andries.

“His [Rawls’] work is an attempt to deduce a theory of justice from first principles – principles that everyone could agree on. His postulation is that all reasonable people would agree that it would be fair to have a society in which the least advantaged people would have the best of all possible deals. In other words, a society where inequality was as low as possible.”

Your “in other words” simply does not hold. Low (or zero) inequality is almost surely not the best possible deal for society’s disadvantaged — the former is a relative measure, while the latter is absolute. This is easiest shown with a simple example, drawing on Rawls’ Veil of Ignorance:

Imagine having a choice between the following two societies to live in, but without knowing which member of that society you will be.

Society One has 4 members, who collectively produce and consume 100 units of social goods (however defined), which they share equally (25 each) amongst each other regardless of individual contributions.

Society Two also has 4 members, but they encourage innovation and productivity by allowing the more innovative members to keep (say) half of their returns for themselves, and sharing the other half with the rest of society. Because of this, Society Two produces and consumes 150 units of social goods, which are distributed as follows: 30 / 35 / 35 / 50.

Now, Society Two has greater inequality than Society One, but its most disadvantaged (relative to the rest of society) still ends up being in a better absolute position (30 vs 25), and should therefore be preferable, no?

“It is, by the way, highly debatable that inequality is needed to grow the size of the cake.”

You’re being far too idealistic. Equality might work in certain smaller communities with a strong sense of the greater good, but game theory will tell you that the “free rider” problem soon brings such a system to a grinding halt… it’s simply human nature.

” It could be that moderate levels of inequality are an inevitable consequence of a dynamic and growing modern society.”

More likely is the reverse, that a dynamic and growing modern society is the inevitable consequence of moderate levels of inequality.

“But many economists would also argue that beyond a certain level, inequality starts being growth-constraining. ”

The law of diminishing marginal utility does predict that it becomes more difficult to incentivise entrepreneurs and innovators once they’ve reached a certain level of wealth, but a progressive tax system takes that into account. Maybe there should be an overall absolute cap on any one individual’s wealth, but this is difficult to implement when different nations compete with tax and other incentives to attract wealthy individuals and corporates.

An interesting current social experiment in this regard is Warren Buffett’s attempt to get as many US billionaires as possbile to voluntarily give away a large percentage of their accumulated wealth. We’ll watch that space!

“In South Africa, the fact that we have such a small middle class, and such a poor working class, is certainly a constraint on growth.”

There is only so much redistribution that one can do from the middle class to the poor before even the middle class packs up and leaves for a more attractive jurisdiction. The only answer, I’m afraid, is to allow for even greater inequality by encouraging entrepreneurship and pouring the increased tax collections into training and education — the only proven long-term path to addressing inequality. Sadly, this is probably the worst performing public sector portfolio in South Africa. Maybe your next conference can focus on just this.

Rawl’s veil of ignorance meant precisely that, a veil of ignorance. You can’t go smuggling your favourite theories about the relationship between inequality and productivity into that scenario to make it go the way you want it to go.

My argument about the growth-limiting impact of high inequality is not idealistic, and is not postulated on the notion of smaller communities with a strong sense of the greater good. It is postulated on the empirical reality that societies with high levels of inequality will also have low levels of aggregate demand. Right now this is one of the key issues constraining the growth of South African manufacturing.

Your statement about the limitations on redistribution is another case in point: high inequality means that you either have insupportably large holes in your social protection system, or an insupportable burden on your fiscus.

That is why you need to have an inclusive, inequality-reducing growth path, in which jobs are created where they are needed – something we have utterly failed to do in South Africa.

Your assertion that a dynamic society is a consequence of moderate levels inequality (instead of the other way round) is just that: an assertion, based on no supporting evidence whatsoever. And in any case, South Africa does not have moderate levels of inequality: it has extreme levels of inequality, levels of inequality that are linked, for instance, to cripplingly poor levels of education among most of our people, which very clearly acts to reduce dynamism and growth.

As for entrepreneurship, a key point made by a number of presentations at our conference was that the problem in South Africa is not a lack of entrepreneurship but the way the dominance of a powerful, sophisticated core economy, characterised by cartels of vertically integrated players who actively crowd out competition, reduces the space for entrepreneurs ‘from below’. The space for rural agro-entrepreneurship and value adding that exists, for example, in India and China and Brazil, just does not exist in South Africa: Pioneer Foods, Shoprite and SAB have already taken all that space. That’s not a problem that you can resolve through training and education.

Andries,

For more reasons than just running out of indents under the previous comment, let’s try a fresh start.

I think we can safely agree that *poverty* in South Africa, and elsewhere, is appalling and needs to be eradicated.

I disagree, however, if you claim that *inequality* in South Africa, and elsewhere, is appalling and needs to be eradicated.

Poverty does not equal inequality. There are poor societies with low levels of inequality (e.g. Swaziland), and there are prosperous societies with high levels of inequality (e.g. the US). Ours happens to be a poor society with high inequality, but eradicating the inequality will not *neccessarily* eradicate the poverty. That’s really the only point I wanted to make, and it really was meant as constructive, practical criticism that might be useful at the frontline of the fight against poverty.

Maybe you mistook my point as being in defense of Capitalism, or proposing that we do nothing. This is most certainly not the case, as should have been clear from my comments in support of a maximally effective (in the Rawlsian sense) progressive tax system — usually anathema to the pure Capitalist or Libertarian.

Something needs to be done… but it needs to be the *right* thing, not just ideologically, but where it matters most — in the lives of the poorest amongst us.

Moreover, there is a very clear and present danger in diverting the attention away from the eradication of poverty to the eradication of inequality, even when done with the best possible intentions. A populist uprising (even if peaceful) to redistribute the assets of the middle class (the upper class being mobile and global enough to largely escape this) will destroy the one chance we have to grow our country out of the hole we find ourselves in.

Everyone ends up losing in such a scenario, which I hope is not the kind of equality you’re after.

How would you eradicate poverty in South Africa without addressing inequality? Any real answer to that question couldn’t just be based on first principles or definitions. It would have to be based on a sense of the nature of inequality in South Africa, and the nature of poverty, and the way in which the are concretely and causally related.

In this respect the key point that a number of presenters made in the conference was precisely that you can’t address poverty in South Africa without addressing the highly unequal power relations that structure our economy and that keep poor people excluded and marginalized. Both poverty and inequality in South Africa are the results (inter alia) of the highly exclusive growth path that we have been on since the 1970s. Poverty cannot be addressed if we don’t find a more inclusive growth path – one that creates enough jobs in the ‘bottom’ of the economy, and which directly addresses the disempowerment faced by the most marginalized people in the society. In fact, presenters like Seeraj Mohammed argued that high levels of inequality are at present becoming growth-inhibiting, and undermines our economic sustainability as a whole.

This is the key issue addressed by the conference: the need for, and the obstacles in the way of, and strategies for achieving inclusive, broad-based growth. Nowhere, either in my blog, or in the conference proceedings, did anyone call for ‘a populist uprising in order to redistribute the assets of the middle class’.

But then, my impression is that you don’t really care what arguments were made at the conference. Otherwise you would take the trouble to look at the papers that were presented there, instead of tilting at straw dolls. Or, if you cared to engage with my arguments at all, you would respond to what I say here about the savage consequences of structural inequality for human relations.

I must say, I find that rather dispiriting. Not only my whole argument, but that of Ms Mji, appears to have passed through you without engaging you in the least.

“How would you eradicate poverty in South Africa without addressing inequality?”

The same way you would eradicate umbrellas on the street without addressing the muddy roads — by focussing on their *common cause*. In fact, you allude to this yourself when you write:

“Both poverty and inequality in South Africa are the results (inter alia) of the highly exclusive growth path that we have been on since the 1970s.”

Correct. They’re both caused by the same thing(s). If you realise this, why do you keep falling back into the “cum hoc ergo propter hoc” logical fallacy by insisting that reducing inequality will also reduce poverty? What if the only (or quickest) path to reducing poverty is actually to allow for *greater* inequality?

“In this respect the key point that a number of presenters made in the conference was precisely that you can’t address poverty in South Africa without addressing the highly unequal power relations that structure our economy and that keep poor people excluded and marginalized.”

What “unequal power relations” do you have in mind here? Business vs labour? South Africa’s restrictive labour legislation is actually a fine example of how good intentions to address “unequal power relations” was successful in doing so only for the lucky minority who now have virtually entrenched jobs (regardless of performance), whilst overall employment has actually shrunk at a time when it needs to grow… Once again the poorest suffer.

“This is the key issue addressed by the conference: the need for, and the obstacles in the way of, and strategies for achieving inclusive, broad-based growth. Nowhere, either in my blog, or in the conference proceedings, did anyone call for ‘a populist uprising in order to redistribute the assets of the middle class’. ”

Of course you didn’t, but many other populist leaders in our country do exactly that, and by deflecting the attention from poverty to inequality, you may just be playing into their hands.

“But then, my impression is that you don’t really care what arguments were made at the conference. Otherwise you would take the trouble to look at the papers that were presented there, instead of tilting at straw dolls.”

Well, it is true that I wasn’t at the conference, and I may not be as emotionally involved in this topic as you and your fellow presenters appear to be, but how is that relevant to the argument? If anything, have you considered that your own views on the topic might benefit from a fresh view from outside the forest? We should all guard against the dangers of groupthink, especially when we feel strongly about the issue at hand.

I was greatly moved by this blog and the comments that followed. Visiting here almost 2 years after your original post. I find it chilling that the causes of poverty and inequality in our society are still not being addressed in any meaningful way.

Ditto. I find that even 2.5 years down the line, this blog brings in a very welcome fresh breath into the long-enduring and (for lack of progress on the poverty/inequality front) progressively dusty structuralist and agency-oriented debates. These often feel so far removed from the lived reality of ordinary lives at either end of the socio-economic class/racial spectrum. Question is: What will it take for South Africa to become ready for the mind-shift / heart-shift you aptly allude to in your blog, Andries?

That’s a good question. I think we have to do two things: on the one hand we have to insist on a confrontation with the harshness of the realities around us. (Earlier in this blog, I wrote about the resonance of ‘the depressive position’ – the difficult and potent moment when one finally has to let go of illusion and face up to reality as it is…. I fear that as a ‘nation’ we are not there yet. ) And on the other it is important to do the imaginative work of mapping the alternatives, and insisting that things can be different.