the heart in exile: persepolis.

OK, so once again I find myself reviewing an animated film based on an acclaimed book I have not read. What’s more, again it is a movie about a young girl’s growing to adulthood. Is this a trend? Oh, well, we will have to wait for Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland to establish that. For now all I will say is that this appears to be a resonant theme: the power of animation to convey a world rendered fantastical, viewed through a little girl’s eyes. Resonant either for me, or for my culture, or both. I wonder why.

OK, so once again I find myself reviewing an animated film based on an acclaimed book I have not read. What’s more, again it is a movie about a young girl’s growing to adulthood. Is this a trend? Oh, well, we will have to wait for Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland to establish that. For now all I will say is that this appears to be a resonant theme: the power of animation to convey a world rendered fantastical, viewed through a little girl’s eyes. Resonant either for me, or for my culture, or both. I wonder why.

The movie, in this case, is Persepolis, the lovely film based on Marjane Satrapi’s autobiographical graphic novels of the same name. It is a very different film, in many ways, from the films I reviewed in my earlier blog: it is not about Wonderland, the ghost world or the hidden world beyond the stairs at all, but about a real country, Iran; and the drama it presents is not a mythopoeic one (connecting with the numinous, encountering sexuality) but political: the impact of war, the risk of imprisonment, the threat to freedom. Perhaps more subtly, while Coraline, Spirited Away and Pan’s Labyrinth are characterised by a deep ambivalence about a femininity which is both feared and desired, in Persepolis it is masculinity which is ambiguous, double edged: the beautiful boys, the brave men, the fatherly God that Marji loves, versus the weak thugs, the bearded fools, the uniformed goons that threaten her world. Conversely what stays with us as viewers (and what saves Marji) is the resilience, the humour, the irreverence of the women, especially that lovely grandmother. But at a deeper level, there are some resonances. Like those three films, Perspepolis pivots centrally around the young woman’s task of growing up (or more precisely, as Le Guin puts it in one of her recent stories, to make a soul); and like them it uses the language of fantasy and animation to to drive home forcefully the way our intentions and imaginations shape our reality, and just how high the stakes are.

In this case, the stakes are life and death. What I found most striking about Persepolis was its evocation of the darkness and fear that becomes part of life when we live with state repression. Well, for me at any rate. I don’t know how a middle-class American or French person would see much of this film, and how they would experience much of the imagery of this film: crowds marching in streets; riot police shooting with live ammunition; government goons balefully patrolling apprehensive citizens; freedom expressed furtively behind closed doors; late night telephone calls with grim, secret news. The stuff of CNN and stories, for those who grew up in the industrialised North (well, for the white, middle class ones anyway) — but all too familiar for anyone who has lived through times of social conflict and authoritarian clampdown. For me the film powerfully evoked memories of the South African 1970s and 1980s. In particular, it reminded me of the surreal reality that takes hold when society is shaped by these issues and conflicts: how war, propaganda, authoritarianism and surveillance impose their unreal, malign normality, depicting a constrictive ideology as the new norm, and rendering everyday things (kisses, boyfriends, visits from uncles) into things contested, fragile, risky, malign, dangerous. And as those who have lived through such times know, what is particularly corrupting about them is how easy it is to start accepting the unacceptable; how easy it is to stop thinking and feeling — and how difficult and frightening to go against the flow.

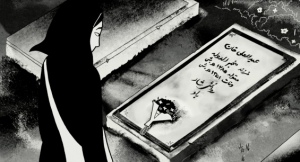

The artwork is central here. It is not only that Satrapi’s visual language is elegant, sparse, and beautiful; it is not even the way in which she appropriates the Western language of comics and graphic novels and links it to the older traditions of Persian art, German Expressionism and radical political cartooning. It is that the possibilities of animation can take the viewer and the teller into places where live action and photography cannot so easily go. The movie’s visual language – the homeliness and affection with which the family members are drawn; the elegance and ornateness in which its Persian roots will from time to time infuse the frame (the falling jasmine blossoms at the end are in themselves worth a minor treatise!); the stark grimness and anger in the renditions of war, repression and death – is central to a very particular artistic, political and emotional task.

The artwork is central here. It is not only that Satrapi’s visual language is elegant, sparse, and beautiful; it is not even the way in which she appropriates the Western language of comics and graphic novels and links it to the older traditions of Persian art, German Expressionism and radical political cartooning. It is that the possibilities of animation can take the viewer and the teller into places where live action and photography cannot so easily go. The movie’s visual language – the homeliness and affection with which the family members are drawn; the elegance and ornateness in which its Persian roots will from time to time infuse the frame (the falling jasmine blossoms at the end are in themselves worth a minor treatise!); the stark grimness and anger in the renditions of war, repression and death – is central to a very particular artistic, political and emotional task.

Here the film works very much in the way that magical realism worked in the political protest novels of the Latin American and Eastern European eighties and nineties. In a context where the power of the media, the pressure of conformity, and the closed moral universe of totalitarian thought try to shape the boundaries of what can be imagined, magical realism was a form that could be used to contest that reality, call its bluff, insist on its inherent surrealism, enlarge the space available for the spirit and the mind.

Marji’s experience is similarly at risk. She is is a historical freak: the child (however distantly) of royalty dreaming of socialist revolution; part of a tiny elite social class trapped in a country sliding into war; a young woman exploring her sexuality in a misogynist, real-life Republic of Gilead; an exiled Persian typecast as a savage by the spoilt Philistines she meets in Germany. Indeed, one of the things the film shows particularly clearly is that this is not simply about the fight between authoritarianism and the desire for freedom; or between the values of cosmopolitan modernity versus those of fundamentalism. True: Marji loves heavy metal, and sings along (pretty badly) to the theme song for Rocky. But what she stands for ultimately is not the west, but the cosmopolitanism, the civilisation, the desire for liberty in Iranian culture: an ancient and rich civilisation misunderstood by the west and hated by Iran’s present-day patriots.

There are not many mirrors in the world that can validate such a reality, such a beleaguered experience. And part of the film’s point is its faithfulness to this reality. It gives us the world as she sees it, limned in the authenticity of her projections. For me, much of the value of Persepolis is that it uses animation as form in a way that allows it to insist on the integrity and value of the emotional experience of political reality: the heart’s experience of war, repression, conflict, choice and loss.

I think all these elements come together most effectively in the early part of the film, where we see the last years of the Shah and the first years of the revolution through the naïve eyes of Marji as a little girl. Like the Hernando brothers, (whose Palomar stories this film powerfully reminds me of) the film is particularly admirable when rendering children’s experience. The storyteller can be fiercely in solidarity with the fierce little girl, while still letting us, the audience, see her innocence, her trustingness, the larger threatening world she still does not understand. Above all, she can set up the central problematic of the story: how will Marji make her soul, how will she become a woman of integrity; how can she keep that fierce, indomitable heart while surviving in this treacherous world?

How indeed? How does Marji handle this potent and difficult terrain? Can she succeed in maintaining the integrity of her heart, as her grandmother repeatedly enjoins her to, under these dire conditions? What does she gain, and what does she lose?

How indeed? How does Marji handle this potent and difficult terrain? Can she succeed in maintaining the integrity of her heart, as her grandmother repeatedly enjoins her to, under these dire conditions? What does she gain, and what does she lose?

The answer is not easy to find. In some way the movie tries to suggest that the story has a happy ending. Marji escapes repressive Teheran; leaves for freedom, as the official synopsis tells us, “optimistic about the future, shaped indelibly by her past”.

But I am not so sure. I think the message the film conveys is altogether bleaker and more grim; and that the story we see is perhaps more about a loss of hope, the impossibility of a certain kind of integrity.

Indeed, my clearest sense in watching the movie, as the narrative went on from its initial, stark beginning, was that it slowly but surely lost steam. The drive and focus of the initial set-up is somewhat dissipated as we follow Marji through the trials and tribulations of early adulthood (she gets depressed; she marries and divorces, a friend dies during a police raid on an illicit party). The young Marji starts off fierce and grandiose; the darling of her radical uncle Anoush’s eye, fantasising that she will be a second prophet, caring for the poor and protecting older women from harm. By the end of the film what is at stake is her personal freedom: the right to drink alcohol, the right to hold a lover’s hand, the right to wear make-up. Now, let’s not disrespect that: such personal freedom is vitally important and eminently worth fighting for, and in any case it is clear that this narrowing of her concern is chiefly an effect of the ever increasing constrictions visited upon Iranian women by misogyny and obtuseness of the priesthood and the regime. But the story shows that even the battle for these tiny freedoms can lead to impossible choices. When the story ends with a second exile, it is an anticlimax, a defeat. Nothing is resolved: Marji escapes repression; but she will never see her grandmother. Freedom, the voice-over sententiously says, always has a price. But the price is greater than that. Marji loses not only her grandmother, but Iran.

It is a harsh and dispiriting message. In the end, the film seems to suggest that the contradictions Marji faces cannot be resolved. The heart cannot hold together all of this: not freedom, beauty, love of family, the desire for justice, love of Persia, and integrity. Something has to give; something, indeed, has to be sacrificed. Marji’s uncle Anoush loses his life. So does the passport-maker’s cousin, raped before she is hanged. Marji, who does not want to die, loses the ground she fights on: leaves for grey, rainy France and the never-ending afterwards of the exile. She cannot dwell in Iran; nor can she dwell in France or Germany. She has to live in Persepolis, an imaginary country, a land that exists only in the space of memory, loss, and desire. A bleak message about bleak times.

Nice Header Image – well done to Masha. Definitely adds something to the subtle-knife theme.

Not too sure about the bluish border though – it distracts a little from the blacks, greys and subtle colours on the knife – but then I’m colour-blind to shades of red/green/brown so don’t take my word for it 😉

Haven’t seen Persepolis yet – it’s definitely on my list. Is there a metaphor of life in general – do we not all start out stark and grandiose and then gently fade into a middle-age of grey reality? Thanks for the blog – this will definitely make me think more when I do get to see it.

if I could have your children I would

I’ll look out for the book and we can time share

Hi Naum. Re your offer. Read Simon Ings’s Hotwire. All kinds of things might be possible but it might be rather complicated 😎

It would be lekker to see the books…

I saw this movie last night, and I cried through most of it –

What struck me was beautiful it is. Apart from the beauty of the story – the love of the uncle for his little niece, between grandmother and grand daughter, of the little brave girl herself – it is just so stunning to look at. And when the story being told is so frightening, and it is told with such lovely images – that becomes a power in itself.

I particularly liked the way she honestly told what it is like to be a child in a country going through turmoil. The way that little Marji wanted to torture a neighbours son with nails, or argues back when her parents say the Shah was not chosen by God. She had within her the seeds for being a revolutionary or a dictator, both.

I agree the film lost some of its vim towards the end. After all those brave deaths, martyrs and exile – the details of her love life and depression seem quite mundane. But I think that is actually also important. That it shows her as a real human woman, not a heroine. Makes it more real, somehow, even if that also means it is also rather sad and depressing, and not hopeful at the end.

Oh and I like the blog design better now also – with a white background. Much better. Dark grey might also work nicely.

How is Marji described as caring and brave………please be specific